سرفصل های مهم

فصل نهم : تعادل خود را حفظ کنید

توضیح مختصر

- زمان مطالعه 0 دقیقه

- سطح خیلی سخت

دانلود اپلیکیشن «زیبوک»

فایل صوتی

برای دسترسی به این محتوا بایستی اپلیکیشن زبانشناس را نصب کنید.

ترجمهی فصل

متن انگلیسی فصل

CHAPTER 9

Manage Yourself

After six great years in the New York office of a large media company, Stephen Erikson was promoted to a senior position at the firm’s Canadian unit. He expected the move from New York to Toronto to be a breeze. After all, Canadians and Americans are pretty much alike. And the city was safe and reputed to have good restaurants and cultural events.

Stephen moved right away, rented a short-term apartment in downtown Toronto, and dove into the new job with his usual energy. His wife, Irene, an accomplished freelance interior designer, put up their co-op apartment for sale and started preparing their two children Katherine, twelve, and Elizabeth, nine for a move in the middle of the school year. Stephen and Irene had talked about postponing moving the children until the end of the school year, four months away, but decided it was too long to have the family separated.

The first hints of trouble in the new job were subtle. Every time he tried to get something done, Stephen felt as if he was wading through molasses. As a lifelong New Yorker accustomed to bluntness in talking about business, he found his new colleagues irritatingly polite and “nice.” Stephen complained to Irene that his colleagues refused to engage in hardheaded discussions about the tough issues. And he couldn’t find the kind of go-to people he had relied on to get things done in New York.

Four weeks after Stephen started the job, Irene joined him in Toronto to look for a new house and school and to scope out prospects for continuing her freelance design work. Stephen was frustrated with the job and irritable. Irene’s unhappiness quickly mounted when she couldn’t find schools to her liking. The children had been happily enrolled in a top-tier private school in New York. They were displeased about moving and had been making Irene’s life miserable. She had calmed them with stories about the adventure of moving to a new country and promises to find them a great new school. Dispirited, she told Stephen she thought they should leave the kids where they were until the end of the year; he agreed.

With Stephen commuting between Toronto and New York, and Irene under pressure as a working single parent, events quickly took their toll. Although Irene visited Toronto for a couple of weekends and continued looking into schools, it became clear that her heart was not in the move. Weekends often were stressful, with the children happy to see Stephen but unhappy about the move. Stephen often arrived back in the office on Mondays tired and found it hard to concentrate, aggravating his difficulties in getting traction and connecting with his colleagues and team. He knew his work performance was suffering, and that further increased his stress.

Eventually he decided to force the issue. Through connections at the company, he found a good school and identified some promising housing prospects. But when he pressed Irene to get going on selling their apartment, the result was the worst fight of their marriage. When it became clear their relationship was being jeopardized, Stephen told the firm he needed either to return to New York or quit.

The life of a leader is always a balancing act, but never more so than during a transition. The uncertainty and ambiguity can be crippling. You don’t know what you don’t know. You haven’t had a chance to build a support network. If you’ve moved, as Stephen did, you’re also in transition personally. If you have a family, they, too, are in transition. Amid all this turmoil, you’re expected to get acclimated quickly and begin to effect positive change in your new organization. For all these reasons, managing yourself is a key transition challenge.

Are you focusing on the right things in the right way? Are you maintaining your energy and keeping your perspective? Are you and your family getting the support you need? Don’t try to go it alone.

Taking Stock

A good place to start is to take stock of how you’re feeling about how things are going in your transition right now. So take a few minutes to look at the “Guidelines for Structured Reflection” (see box) to assess how you’re doing.

Guidelines for Structured Reflection

How Do You Feel So Far?

On a scale of high to low, do you feel:

Excited? If not, why not? What can you do about it?

Confident? If not, why not? What can you do about it?

In control of your success? If not, why not? What can you do about it?

What Has Bothered You So Far?

With whom have you failed to connect? Why?

Of the meetings you’ve attended, which has been the most troubling? Why?

Of all that you’ve seen or heard, what has disturbed you most? Why?

What Has Gone Well or Poorly?

Which interactions would you handle differently if you could? Which exceeded your expectations? Why?

Which of your decisions have turned out particularly well? Not so well? Why?

What missed opportunities do you regret most? Was a better result blocked primarily by you, or by something beyond your control?

Now focus on the biggest challenges or difficulties you face. Be honest with yourself. Are your difficulties situational, or do their sources lie within you? Even experienced and skilled people may blame problems on the situation rather than on their own actions. The net effect is that they are less proactive than they could be.

Now take a step back. If things are not going completely the way you want, why is that? Is it only the inevitable emotional roller coaster you will experience when taking a new role? It’s inevitable that your initial enthusiasm will wane as the excitement of taking on a new challenge wears off and the reality sets in of the challenges you face. It’s common for leaders to go into a valley three to six months after taking a new role. The good news is that you’re virtually certain to come out the other side—as long as you’re applying your 90-day plan, of course.

It’s also possible, however, that the difficulties you face are the result of deeper personal vulnerabilities that could take you offtrack. That’s because transitions tend to amplify your weaknesses. So look at the following list of potentially dysfunctional behaviors, and ask yourself (and, if it’s safe to do so, others who know you well and will give you honest feedback) whether you potentially are suffering from any of these syndromes.

Undefended boundaries. If you fail to establish solid boundaries defining what you are willing and not willing to do, the people around you—bosses, peers, and direct reports—will take whatever you have to give. The more you give, the less they will respect you and the more they will ask of you—another vicious cycle. Eventually you will feel angry and resentful that you’re being nibbled to death, but you will have no one to blame but yourself. If you cannot establish boundaries for yourself, you cannot expect others to do it for you.

Brittleness. The uncertainty inherent in transitions can exacerbate rigidity and defensiveness, especially in new leaders with a high need for control. Often the result is overcommitment to failing courses of action. You make a call prematurely and then feel unable to back away from it without losing credibility. The longer you wait, the harder it is to admit you were wrong, and the more calamitous the consequences. Or perhaps you decide that your way of accomplishing a particular goal is the only way. As a result, your rigidity disempowers people who have equally valid ideas about how to achieve the same goal.

Isolation. To be effective, you must be connected to the people who make action happen and to the subterranean flow of information. It’s surprisingly easy for new leaders to end up isolated, and isolation can creep up on you. It happens because you don’t take the time to make the right connections, perhaps by relying overmuch on a few people or on official information. It also happens if you unintentionally discourage people from sharing critical information with you. Perhaps they fear your reaction to bad news, or they see you as having been captured by competing interests. Whatever the reason, isolation breeds uninformed decision making, which damages your credibility and further reinforces your isolation.

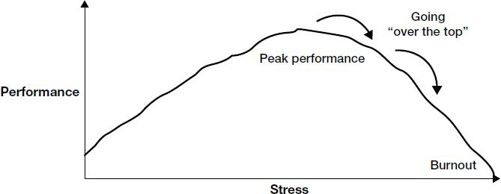

Work avoidance. You will have to make tough calls early in your new job. Perhaps you must make major decisions about the direction of the business based on incomplete information. Or perhaps your personnel decisions will have a profound impact on people’s lives. Consciously or unconsciously, you may choose to delay by burying yourself in other work or fool yourself into believing that the time isn’t ripe to make the call. The result is what leadership thinkers have termed work avoidance: the tendency to avoid taking the bull by the horns, which results in tough problems becoming even tougher.1 All these syndromes can contribute to dangerous levels of stress. Not all stress is bad. In fact, there is a well-documented relationship between stress and performance known as the Yerkes-Dodson curve, illustrated in figure 9-1.2 Whether stress is self-generated or externally imposed, you need some stress (often in the form of positive incentives or consequences from inaction) to be productive. Without it, not much happens—you stay in bed munching chocolates.

FIGURE 9-1

Yerkes-Dodson human performance curve

As you begin to experience pressure, your performance improves, at least at first. Eventually you reach a point (which varies from person to person) at which further demands, in the form of too many balls to juggle or too heavy an emotional load, start to undermine your performance. This dynamic creates more stress, further reducing your performance and creating a vicious cycle as you go over the top of your stress curve. Rarely, exhaustion sets in and you burn out. Much more common is chronic underperformance: you work harder and achieve less. This is what happened to Stephen.

Understanding the Three Pillars of Self-Management

If you have these sorts of weaknesses, what can you do about it? You must vigorously engage in self-management, a personal practice that is built on a foundation with three pillars. The first pillar is adoption of the success strategies presented in the previous eight chapters. The second pillar is creation and enforcement of some personal disciplines. The third pillar is formation of support systems, at work and at home, that help you maintain your balance.

Pillar 1: Adopt 90-Day Strategies

The strategies spelled out in the previous eight chapters represent a template for how to prepare, learn, set priorities, create plans, and direct action to build momentum. When you see these strategies work and when you get some early successes under your belt, you will feel more confident and energized by what you’re accomplishing. As you progress through your transition, think about the challenges you’re facing in light of the core challenges summarized in table 9-1, and identify the chapters to which you want to return.

TABLE 9-1

Assessment of core challenges

Core challenge Diagnostic questions

Prepare yourself. Are you adopting the right mind-set for your new job and letting go of the past?

Accelerate your learning. Are you figuring out what you need to learn, whom to learn it from, and how to speed up the learning process?

Match your strategy to the situation. Are you diagnosing the type of transition you face and the implications for what to do and what not to do?

Negotiate success. Are you building your relationship with your new boss, managing expectations, and marshaling the resources you need?

Secure early wins. Are you focusing on the vital priorities that will advance your long-term goals and build your short-term momentum?

Achieve alignment. Are you identifying and fixing frustrating misalignments of strategy, structure, systems, and skills?

Build your team. Are you assessing, restructuring, and aligning your team to leverage what you’re trying to accomplish?

Create alliances. Are you building a base of internal and external support for your initiatives so that you’re not pushing rocks uphill?

Pillar 2: Develop Personal Disciplines

Knowing what you should be doing is not the same thing as doing it. Ultimately, success or failure emerges from the accumulation of daily choices that propel you in productive directions or push you off a cliff. This is the territory of the second pillar of personal efficacy: personal disciplines.

Personal disciplines are the regular routines you enforce on yourself ruthlessly. What specific disciplines are the highest priorities for you? It depends on what your strengths and weaknesses are. You may have a great deal of insight into yourself, but you should also consult others who know you well and whom you trust. (Some 360-degree feedback can be useful here.) What do they see as your strengths and, crucially, your potential weak spots?

Use the following list of personal disciplines to stimulate your thinking about routines you need to develop.

Plan to Plan. Do you devote time daily and weekly to a plan-work-evaluate cycle? If not, or if you do so irregularly, you need to be more disciplined about planning. At the end of each day, spend ten minutes evaluating how well you met your goals and then planning for the next day. Do the same thing at the end of each week. Get into the habit of doing this. Even if you fall behind, you will be more in control.

Focus on the Important. Do you devote time each day to the most important work that needs to be done? It’s easy for the urgent to crowd out the important. You get caught up in the flow of transactions phone calls, meetings, e-mail and never find time to focus on the medium term, let alone the long term. If you’re having trouble getting the real work done, discipline yourself to set aside a particular time each day, even as little as half an hour, when you will close the door, turn off your phone, ignore e-mail, and focus, focus, focus.

Judiciously Defer Commitment. Do you make commitments on the spur of the moment and later regret them? Do you blithely agree to do things in the seemingly remote future, only to kick yourself when the day arrives and your schedule is full? If you do, you must learn to defer commitment. Whenever anybody asks you to do something, say, “Sounds interesting. Let me think about it and get back to you.” Never say yes on the spot. If you’re being pressed (perhaps by someone who knows your vulnerability to such pressure), say, “Well, if you need an answer now, I’ll have to say no. But if you can wait, I will give it more thought.” Begin with no; it’s easy to say yes later. It’s difficult (and damaging to your reputation) to say yes and then change your mind. Keep in mind that people will ask you to make commitments far in advance, knowing that your schedule will look deceptively open.

Go to the Balcony. Do you find yourself getting too caught up in emotional escalation in difficult situations? If you do, discipline yourself to stand back, take stock from fifty thousand feet, and then make productive interventions. Leading authorities in the fields of leadership and negotiation have long praised the value of “going to the balcony” in this way.3 It can be tough to do this, especially when the stakes are high and you’re emotionally involved. But with discipline and practice, it is a skill that can be cultivated.

Check In with Yourself. Are you as aware as you need to be of your reactions to events during your transition? If not, discipline yourself to engage in structured reflection about your situation. For some new leaders, structured self-assessment means jotting down a few thoughts, impressions, and questions at the end of each day. For others, it means setting aside time each week to assess how things are going. Find an approach that suits your style, and discipline yourself to use it regularly. Work to translate the resulting insights into action.

Recognize When to Quit. To adapt an old saw, transitions are marathons and not sprints. If you find yourself going over the top of your stress curve more than occasionally, you must discipline yourself to know when to quit. This is easy to say and hard to do, of course, especially when you’re up against a deadline and think one more hour might make all the difference. It may, in the short term, but the long-term cost could be steep. Work hard at recognizing when you’re at the point of diminishing returns, and take a break of whatever sort refreshes you.

Pillar 3: Build Your Support Systems

The third pillar of self-management is solidifying your personal support systems. This means asserting control in your local environment, stabilizing the home front, and building a solid advice-and-counsel network.

Assert Control Locally. It’s hard to focus on work if the basic infrastructure that supports you is not in place. Even if you have more pressing worries, move quickly to get your new office set up, develop routines, clarify expectations with your assistant, and so on. If necessary, assemble a set of temporary resources to tide you over until the permanent systems are operational.

Stabilize the Home Front. It’s a fundamental rule of warfare to avoid fighting on too many fronts. For new leaders, this means stabilizing the home front so that you can devote the necessary attention to work. You cannot hope to create value at work if you’re destroying value at home. This is the fundamental mistake that Stephen made.

If your new position involves relocation, your family is also in transition. Like Irene, your spouse may be making a job transition, too, and your children may have to leave their friends and change schools. In other words, the fabric of your family’s life may be disrupted just when you most need support and stability. The stresses of your professional transition can amplify the strain of your family’s transition. Also, family members’ difficulties can add to your already heavy emotional load, undermining your ability to create value and lengthening the time it takes for you to reach the break-even point.

So focus on accelerating the family transition, too. The starting point is to acknowledge that your family may be unhappy, even resentful, about the transition. There is no avoiding disruption, but it can be helpful to talk about it and work through the sense of loss together.

Beyond that, here are some guidelines that can help smooth your family’s transition:

Analyze your family’s existing support system. Moving severs your ties with the people who provide essential services for your family: doctors, lawyers, dentists, babysitters, tutors, coaches, and more. Do a support-system inventory, identify priorities, and invest in finding replacements quickly.

Get your spouse back on track. Your spouse may quit his old job with the intention of finding a new one after relocating. Unhappiness can fester if the search is slow. To accelerate it, negotiate up front with your company for job-search support, or find such support shortly after moving. Above all, don’t let your spouse defer getting going.

Time the family move carefully. For children, it is substantially more difficult to move in the middle of a school year. Consider waiting until the end of the school year to move your family. The price, of course, is separation from your loved ones and the wear and tear of commuting. If you do this, however, be sure that your spouse has extra support to help ease the burden. Being a single parent is hard work.

Preserve the familiar. Reestablish familiar family rituals as quickly as possible, and maintain them throughout the transition. Help from favorite relatives, such as grandparents, also makes a difference.

Invest in cultural familiarization. If you move internationally, get professional advice about the cross-cultural transition. Isolation is a far greater risk for your family if there are language and cultural barriers.

Tap into your company’s relocation service, if it has one, as soon as possible. Corporate relocation services are typically limited to helping you find a new home, move belongings, and locate schools, but such help can make a big difference.

There is no avoiding pain if you decide to move your family. But there is much you can do to minimize it and to accelerate everyone’s transitions.

Build Your Advice-and-Counsel Network. No leader, no matter how capable and energetic, can do it all. You need a network of trusted advisers within and outside the organization with whom to talk through what you’re experiencing. Your network is an indispensable resource that can help you avoid becoming isolated and losing perspective. As a starting point, you need to cultivate three types of advisers: technical advisers, cultural interpreters, and political counselors (see table 9-2).

You also need to think hard about the mix of internal and external advisers you want to cultivate. Insiders know the organization, its culture and politics. Seek out people who are well connected and whom you can trust to help you grasp what is really going on. They are a priceless resource.

TABLE 9-2

Types of advisers

At the same time, insiders cannot be expected to give you dispassionate or disinterested views of events. Thus, you should augment your internal network with outside advisers and counselors who will help you work through the issues and decisions you face. They should be skilled at listening and asking questions, have good insight into the way organizations work, and have your best interests at heart.

Use table 9-3 to assess your advice-and-counsel network. Analyze each person in terms of the domains in which she assists you technical adviser, cultural interpreter, political counselor as well as whether each is an insider or an outsider.

Now take a step back. Will your existing network provide the support you need in your new role? Don’t assume that people who have been helpful in the past will continue to be helpful in your new situation. You will encounter different problems, and former advisers may not be able to help you in your new role. As you attain higher levels of responsibility, for example, the need for good political counsel typically increases dramatically.

TABLE 9-3

Assessment of your advice-and-counsel network

You should also be thinking ahead. Because it takes time to develop an effective network, it’s not too early to focus on what sort of network you will need in your next job. How will your needs for advice change?

To develop an effective support network, you need to make sure you have the right help and your support network is there when you need it. Does your support network have the following qualities?

The right mix of technical advisers, cultural interpreters, and political counselors.

The right mix of internal and external advisers. You want honest feedback from insiders and the dispassionate perspective of outside observers.

External supporters who are loyal to you as an individual, not to your new organization or unit. Typically, these are long-standing colleagues and friends.

Internal advisers who are trustworthy, whose personal agendas don’t conflict with yours, and who offer straight and accurate advice.

Representatives of key constituencies who can help you understand their perspectives. You do not want to restrict yourself to one or two points of view.

Staying on Track

You will have to fight to manage yourself every single day. Ultimately, your success or failure will flow from all the small choices you make along the way. These choices can create momentum for the organization and for you or they can result in vicious cycles that undermine your effectiveness. Your day-to-day actions during your transition establish the pattern for all that follows, not only for the organization but also for your personal efficacy and ultimately your well-being.

MANAGE YOURSELF CHECKLIST

What are your greatest vulnerabilities in your new role? How do you plan to compensate for them?

What personal disciplines do you most need to develop or enhance? How will you do that? What will success look like?

What can you do to gain more control over your local environment?

What can you do to ease your family’s transition? What support relationships will you have to build? Which are your highest priorities?

What are your priorities for strengthening your advice-and-counsel network? To what extent do you need to focus on your internal network? Your external network? In which domain do you most need additional support technical, cultural, political, or personal?

مشارکت کنندگان در این صفحه

تا کنون فردی در بازسازی این صفحه مشارکت نداشته است.

🖊 شما نیز میتوانید برای مشارکت در ترجمهی این صفحه یا اصلاح متن انگلیسی، به این لینک مراجعه بفرمایید.