سرفصل های مهم

فصل هفتم : گروه خود را تشکیل دهید

توضیح مختصر

- زمان مطالعه 0 دقیقه

- سطح خیلی سخت

دانلود اپلیکیشن «زیبوک»

فایل صوتی

برای دسترسی به این محتوا بایستی اپلیکیشن زبانشناس را نصب کنید.

ترجمهی فصل

متن انگلیسی فصل

CHAPTER 7

Build Your Team

When Liam Geffen was appointed to lead a troubled business unit of a process automation company, he knew he was in for an uphill climb. The extent of the challenge became clearer when he read the previous year’s performance evaluations for his new team. Everyone was either outstanding or marginal; there was nobody in between. It seemed his predecessor had played favorites.

Conversations with his new direct reports and a thorough review of operating results confirmed Liam’s suspicion that the performance evaluations were skewed. In particular, the VP of marketing seemed reasonably competent but by no means a minor god. Unfortunately, he believed his own press. The VP of sales struck Liam as a solid performer who had been scapegoated for poor judgment calls by Liam’s predecessor. The relationship between marketing and sales was understandably tense.

Liam recognized that one or both of the VPs would probably have to go. He met with each of them separately and bluntly told them how he viewed their performance ratings. He then laid out detailed two-month plans for each. Meanwhile, he and his VP for human resources quietly launched outside searches for both positions. Liam also held skip-level meetings with midlevel people to assess the depth of talent and to look for promising candidates for the top jobs.

By the end of his third month, Liam had signaled to the marketing VP that he would not make it; he soon left and was replaced by one of his direct reports. Meanwhile, the head of sales had risen to Liam’s challenge. Now Liam was confident he had strong performers in these two key positions and was ready to move forward.

Liam recognized that he couldn’t afford to have the wrong people on his team. If, like most new leaders, you inherit a group of direct reports, it is essential to build your team to marshal the talent you need to achieve superior results. The most important decisions you make in your first 90 days will probably be about people. If you succeed in creating a high-performance team, you can exert tremendous leverage in value creation. If not, you will face severe difficulties, for no leader can hope to achieve much alone. Bad early personnel choices will almost certainly haunt you.

But even though finding the right people is essential, it is not enough. Begin by assessing existing team members (direct and indirect reports) to decide what changes you need to make. Then devise a plan for getting new people and moving the people you retain into the right positions—without doing too much damage to short-term performance in the process. Even this is not enough. You still need to align and motivate your team members to propel them in desired directions. Finally, you must establish new processes to promote teamwork.

Avoiding Common Traps

Many new leaders stumble when it comes to building their teams. The result may be a significant delay in reaching the break-even point, or it may be outright derailment. These are some of the characteristic traps into which you can fall: Criticizing the previous leadership. There is nothing to be gained by criticizing the people who led the organization before you arrived. This doesn’t mean that you need to condone poor past performance, nor does it mean that you can’t highlight problems. Of course you need to evaluate the impact of previous leadership, but rather than point out others’ mistakes, concentrate on assessing current behavior and results and on making the changes necessary to support improved performance.

Keeping the existing team too long. Unless you are in a start-up, you do not get to build a team from scratch; you inherit a team and must mold it into what you need to achieve your A-item priorities. Some leaders make major changes in their teams too precipitously, but it is more common to keep people longer than is wise. Whether because they’re afflicted with hubris (“These people have not performed well because they lacked a leader like me”) or because they shy away from tough personnel calls, leaders end up with less-than-outstanding teams. This means they and the other strong performers must shoulder more of the load themselves. The extent of team change and the time frame for making shifts depends on the STARS situation you confront; it may be shorter in a turnaround, and longer in a realignment situation. Also, there may be constraints on your ability to make changes; you may have to accept that and figure out how to get the most out of the people you’ve inherited—for example, by defining roles. In any case, you should establish deadlines for reaching conclusions about your team and taking action within your 90-day plan, and then stick to them.

Not balancing stability and change. Building a team you’ve inherited is like repairing a leaky ship in mid-ocean. You will not reach your destination if you ignore the necessary repairs, but you do not want to try to change too much too fast and sink the ship. The key is to find the right balance between stability and change. First and foremost, focus only on truly high-priority personnel changes early on. If you can make do for a while with a B-player, then do so.

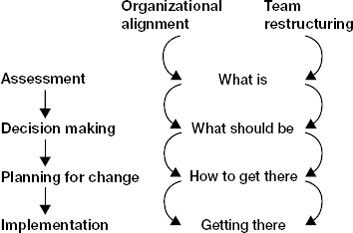

Not working on organizational alignment and team development in parallel. A ship’s captain cannot make the right choices about his crew without knowing the destination, the route, and the ship. Likewise, you can’t build your team in isolation from changes in strategic direction, structure, processes, and skill bases. Otherwise, you could end up with the right people in the wrong jobs. As figure 7-1 illustrates, your efforts to assess the organization and achieve alignment should go on in parallel with assessment of the team and necessary personnel changes.

Not holding on to the good people. One experienced manager shared hard-won lessons about the dangers of losing good people. “When you shake the tree,” she said, “good people can fall out, too.” Her point is that uncertainty about who will and will not be on the team can lead your best people to move elsewhere. Although there are constraints on what you can say about who will stay and who will go, you should look for ways to signal to the top performers that you recognize their capabilities. A little reassurance goes a long way.

Undertaking team building before the core is in place. It is tempting to launch team-building activities right away, but this approach poses a danger; it strengthens bonds in a group, some of whose members may be leaving. So avoid explicit team-building activities until the team you want is largely in place. This does not mean, of course, that you should avoid meeting as a group. Just keep the focus on the business.

Making implementation-dependent decisions too early. When successful implementation of key initiatives requires buy-in from your team, you should judiciously defer making decisions until the core members are in place. Of course there will be decisions you cannot afford to delay, but it can be counterproductive to make decisions that commit new people to courses of action they had no part in defining. Carefully weigh the benefits of moving quickly on major initiatives against the lost opportunity of gaining buy-in from the people you will bring on board later.

Trying to do it all yourself. Finally, keep in mind that restructuring a team is fraught with emotional, legal, and company policy complications. Do not try to undertake this on your own. Find out who can best advise you and help you chart a strategy. The support of a good HR person is indispensable to any effort to restructure a team.

Assuming you avoid these traps, what do you need to do to build your team? Start by rigorously assessing the people you inherited, and then plan to evolve the team into what you need it to be. In parallel with this, work to align the team with your strategic direction and early-win priorities, and put in place the performance-management and decision-making processes you need to lead effectively.

Assessing Your Team

You likely will inherit some outstanding performers (A-players), some average ones (B-players), and some who are simply not up to the job (C-players). You will also inherit a group with its own internal dynamics and politics; some members may even have hoped for your job. During your first 30 to 60 days (depending on the STARS mix you inherited), you need to sort out who’s who, what roles people have played, and how the group has worked in the past.

Establish Your Evaluative Criteria

You will inevitably find yourself forming impressions of team members as you meet them and digest results and performance reviews. Don’t suppress these early reactions, but be sure to step back from them and undertake a more rigorous evaluation.

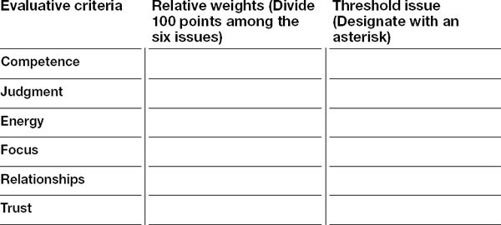

The starting point is to be conscious of the criteria you will explicitly or implicitly use to evaluate people who report to you. Consider these six criteria: Competence. Does this person have the technical competence and experience to do the job effectively?

Judgment. Does this person exercise good judgment, especially under pressure or when faced with making sacrifices for the greater good?

Energy. Does this team member bring the right kind of energy to the job, or is she burned out or disengaged?

Focus. Is this person capable of setting priorities and sticking to them, or prone to riding off in all directions?

Relationships. Does this individual get along with others on the team and support collective decision making, or is he difficult to work with?

Trust. Can you trust this person to keep her word and follow through on commitments?

To get a quick read on the criteria you use, fill out table 7-1. Divide 100 points among the six criteria according to the relative weight you place on them when you evaluate direct reports. Record those numbers in the middle column, making sure they add up to 100. Now identify one of these criteria as your threshold issue, meaning that if a person does not meet a basic threshold on that dimension, nothing else matters. Label your threshold issue with an asterisk in the right-hand column.

Now step back. Does this analysis accurately represent the values you apply when you evaluate people on your team? If so, does it suggest any potential blind spots in the way you evaluate people? It is worthwhile to spend some time thinking about the criteria you will use. Having done so, you will be better prepared to make a rigorous and systematic evaluation.

Check Your Assumptions

Your assessments are likely to reflect assumptions you hold about what you can and can’t change in the people who work for you. If you score relationships low and judgment high, for example, you may think that relationships within your team are something you can influence, whereas you cannot influence judgment. Likewise, you may have designated trust as a threshold issue—many leaders do—because you believe you must be able to trust those who work for you and because you think trustworthiness is a trait that cannot be changed. You may be right in these assumptions, but it’s essential that you be conscious you are making them.

Factor In Functional Expertise

If you’re managing a team whose members have diverse functional expertise—such as marketing, finance, operations, and R&D—you need to get a handle on their competence in their respective areas. This task can be daunting, especially for first-time enterprise leaders. If you’re an insider, try to solicit the opinions of people you respect in each function who know the individuals on your team. (For more on the transition to enterprise leadership and its challenges, see Michael Watkins, “How Managers Become Leaders,” Harvard Business Review, June 2012.) If you’re entering an enterprise leader role, consider developing your own templates for evaluating people in functions such as marketing, sales, finance, and operations. A good template includes function-specific key performance indicators (KPIs), what the KPIs should and should not show, key questions to ask, and warning signs. To develop each template, talk to experienced enterprise leaders about what they look for in these functions.

Factor In the Extent of Teamwork

The weights you apply in evaluation should vary depending on the work your direct reports are doing. Suppose, for example, that you’re taking a new job as vice president of sales, managing a geographically scattered group of regional sales managers. How would your criteria for evaluating this group differ from those you would apply if you had been named to lead a new-product development project?

These jobs differ sharply in the extent to which your direct reports operate independently. If your direct reports operate more or less independently, their capacity to work together will be far less important than if you were managing an interdependent product development team. In situations like this, it may be perfectly acceptable to have a high-performing group rather than a true team.

Factor In the STARS Mix

The criteria you apply may also depend on your STARS portfolio—the mix of start-up, turnaround, accelerated-growth, realignment, or sustaining-success situations you have inherited. In a sustaining-success situation, for example, you may have the time to develop one or two high-potential members of your team. It may be OK if they currently are B-players, if you are confident you can get them to the A-player level.1 In a turnaround, by contrast, you need people who can perform at the A-player level right away.

You also should evaluate people based on their STARS experience and capabilities as well as their match to the situation at hand. Suppose, for example, you’re taking over a business that was once very successful, started to slide, and wasn’t successfully realigned. Now you’ve been brought in to turn it around. You may have inherited people who would be A-performers in sustaining-success or realignment situations but who are not the types of leaders you need in a turnaround.

Factor In the Criticality of Positions

Finally, your evaluations of team members should depend on how critical their positions are. As you make your assessments, keep in mind it’s not only about players but also about positions.2 So take some time to assess how important the various positions held by your direct and indirect reports are to your success. If it helps, list the positions and assess the criticality of each on a 1–10 scale. Then keep these assessments in mind as you evaluate the people you inherited.

It’s important to do this, because it takes a lot of energy to make changes on your team. It may be all right if you find that you have a B-player in a position that isn’t high on the critical list, but not at all acceptable if the position is critical.

Assess Your People

When you begin to assess each team member using the criteria and assessments of position criticality you have developed, the first test is whether any of them fail to meet your threshold requirements. If so, begin planning to replace them. However, merely surviving the basic hurdle does not mean they are keepers. Go on to the next step: evaluate their strengths and weaknesses, factoring in the relative value you assign to each criterion. Now who makes the grade, and who does not?

Meet one-on-one with each member of your new team as soon as possible. Depending on your style, these early meetings might take the form of informal discussions, formal reviews, or a combination, but your own preparation and focus should be standardized: Prepare for each meeting. Review available personnel history, performance data, and other appraisals. Familiarize yourself with each person’s technical or professional skills so that you can assess how he functions on the team.

Create an interview template. Ask people the same set of questions, and see how their answers vary. Here are sample questions.

– What are the strengths and weaknesses of our existing strategy?

– What are the biggest challenges and opportunities facing us in the short term? In the medium term?

– What resources could we leverage more effectively?

– How could we improve the way the team works together?

– If you were in my position, what would your priorities be?

Look for verbal and nonverbal clues. Note choices of words, body language, and hot buttons.

– Notice what the individual does not say. Does the person volunteer information, or do you have to extract it? Does the person take responsibility for problems in her area? Make excuses? Subtly point fingers at others?

– How consistent are the individual’s facial expressions and body language with his words?

– What topics elicit strong emotional responses? These hot buttons provide clues to what motivates the individual and what kinds of changes she would be energized by.

– Outside these one-on-one meetings, notice how the individual relates to other team members. Do relations appear cordial and productive? Tense and competitive? Judgmental or reserved?

Test Their Judgment

Make sure you are assessing judgment and not only technical competence or basic intelligence. Some very bright people have lousy business judgment, and some people of average competence have extraordinary judgment. It is essential to be clear about the mix of knowledge and judgment you need from key people.

One way to assess judgment is to work with a person for an extended time and observe whether he is able to (1) make sound predictions and (2) develop good strategies for avoiding problems. Both abilities draw on an individual’s mental models, or ways of identifying the essential features and dynamics of emerging situations and translating those insights into effective action. This is what expert judgment is all about. The problem, of course, is that you don’t have much time, and it can take a while to find out whether someone did or did not make good predictions. Fortunately, there are ways you can accelerate this process.

One way is to test people’s judgment in a domain in which feedback on their predictions will emerge quickly. Experiment with the following approach. Ask individuals about a topic they’re passionate about outside work. It could be politics or cooking or baseball; it doesn’t matter. Challenge them to make predictions: “Who do you think is going to do better in the debate?” “What does it take to bake a perfect soufflé?” “Which team will win the game tonight?” Press them to commit themselves; unwillingness to go out on a limb is a warning sign in itself. Then probe why they think their predictions are correct. Does the rationale make sense? If possible, follow up to see what happens.

What you’re testing is a person’s capacity to exercise expert judgment in a particular domain. Someone who has become an expert in a private domain is likely to have done so in her chosen field of business, too, given enough passion about it. However you do it, the key is to find ways, beyond just waiting to see how people perform on the job, to probe for the hallmarks of expertise.

Assess the Team as a Whole

In addition to evaluating individual team members, assess how the entire group works. Use these techniques for spotting problems in the team’s overall dynamics: Study the data. Read reports and minutes of team meetings. If your organization conducts climate or morale surveys of individual units, examine these as well.

Systematically ask questions. Assess the individual responses to the common set of questions you asked when you met with individual team members. Are their answers overly consistent? If so, this may suggest an agreed-on party line, but it could also mean that everyone genuinely shares the same impressions of what’s going on. It will be up to you to evaluate what you observe. Do the responses show little consistency? If so, the team may lack coherence.

Probe group dynamics. Observe how the team interacts in your early meetings. Do you detect any alliances? Particular attitudes? Leadership roles? Who defers to whom on a given topic? When one person is speaking, do others roll their eyes or otherwise express disagreement or frustration? Pay attention to these signs to test your early insights and detect coalitions and conflicts.

Evolving Your Team

Once you’ve evaluated individual team members’ capabilities, factoring in functional expertise, teamwork requirements, the STARS portfolio, and the criticality of positions, the next step is to figure out how best to deal with each person. By the end of roughly the first 30 days, you should be able to provisionally assign people to one of the following categories: Keep in place. The person is performing well in her current job.

Keep and develop. The individual needs development, and you have the time and energy to do it.

Move to another position. The person is a strong performer but is not in a position that makes the most of his skills or personal qualities.

Replace (low priority). The person should be replaced, but the situation is not urgent.

Replace (high priority). The person should be replaced as soon as possible.

Observe for a while. This person is still a question mark, and you need to learn more before you can make a definitive judgment about them.

These assessments need not be absolutely irreversible, but you should feel 90-plus percent confident in them. If you remain uncertain about someone, leave her in the “observe” category. As time goes on and you learn more, you can revise and refine your assessments.

Consider Alternatives

You may be tempted to begin right away to act on high-priority replacement decisions. But take a moment first to consider alternatives. Letting an employee go can be difficult and time-consuming. Even if poor performance is well documented, the termination process can take months or longer. If there is no paper trail regarding poor performance, it will take time to document.

In addition, your ability to replace someone at all may depend on a host of factors, including legal protections, cultural norms, and political alliances. Sometimes it simply is not possible to replace someone, even if he is performing miserably. If this is the case, you must figure out how to play the hand you were dealt as well as possible.

Fortunately, you have alternatives. Often, a poor performer will decide to move on of her own accord in response to a clear message from you. Alternatively, you can work with human resources to shift the person to a more suitable position: Shift her role. Move her to a position on the team that better suits her skills. This is unlikely to be a permanent solution for a problem performer, but it can help you work through the short-term problem of keeping the organization running while you look for the right person to fill the slot.

Move her out of the way. If she simply can’t contribute productively or is a disruptive or dispiriting influence, then it is better to have her doing nothing than destroying value. Consider shrinking her responsibilities significantly. This also has the virtue of sending a strong signal to her about your view of her contributions, which may help her see that it would be best to move on.

Move her elsewhere in the organization. Help the person find a suitable position in the larger organization. Sometimes, if handled well, this move can benefit you, the individual, and the organization overall, but don’t pursue this solution unless you are genuinely convinced the person can perform well in the new situation. Simply shifting a problem performer onto someone else’s shoulders will damage your reputation.

Develop Backups

To keep your team functioning while you build the best possible long-term configuration, you may need to keep an underperformer on the job while searching for a replacement. As soon as you are reasonably sure that someone is not going to make it, begin looking discreetly for a successor. Evaluate other people on your team and elsewhere in the organization for the potential to move up. Use skip-level meetings and regular reporting sessions to evaluate the talent pool. Ask human resources to launch a search.

Treat People Respectfully

During every phase of the team-evolution process, take pains to treat everyone with respect. Even if people in your unit agree that a particular person should be replaced, your reputation will suffer if they view your actions as unfair. Do what you can to show people the care with which you are assessing team members’ capabilities and the fit between jobs and individuals. Your direct reports will form lasting impressions of you based on how you manage this part of your job.

Aligning Your Team

Having the right people on the team is essential, but it’s not enough. To achieve your agreed-to priorities and secure early wins, you need to define how each team member can best support those key goals. This process calls for breaking down large goals into their components and working with your team to assign responsibility for each element. Then it calls for making each individual accountable for managing his goals. How do you encourage accountability?

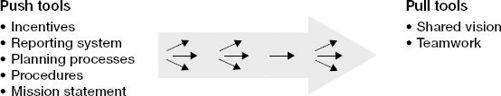

As illustrated in figure 7-2, a blend of push and pull tools works best to align and motivate a team. Push tools, such as goals, performance measurement systems, and incentives, motivate people through authority, loyalty, fear, and expectation of reward for productive work. Pull tools, such as a compelling vision, inspire people by invoking a positive and exciting image of the future.

The mix of push and pull you use will depend on your assessment of how people on your team prefer to be motivated. Your high-energy go-getters may respond more enthusiastically to pull incentives. With more methodical and risk-averse folks, push tools may prove more effective.

The right mix also will depend on the STARS situations you’re dealing with. Turnarounds typically provide plenty of push. The problem teaches people that something needs to be done. In realignment situations, however, it may be challenging to create a sense of urgency. When this is the case, focus more attention on the pull side of the equation—for example, by defining a compelling vision for what the organization could become.

Define Goals and Performance Metrics

On the push side, establishing—and sticking to—clear and explicit performance metrics is the best way to encourage accountability. Select performance measures that will let you know as clearly as possible whether a team member has achieved her goals.

Avoid ambiguously defined goals, such as “Improve sales” or “Decrease product development time.” Instead, define goals in terms that can be quantified. Examples include “Increase sales of product X by 15 to 30 percent over the fourth quarter of this year,” or “Decrease development time on product line Y from twelve months to six months within the next two years.” Align Incentives

A baseline question to ask yourself is how best to incentivize team members to achieve desired goals. What mix of monetary and nonmonetary rewards will you employ?

It is equally important to decide whether to base rewards more on individual or collective performance. This decision is linked to your assessment of whether you need true teamwork. If so, put more emphasis on collective rewards. If it is sufficient to have a high-performing group, then place more emphasis on individual performance.

It’s important to strike the right balance. If your direct reports work essentially independently and if the group’s success hinges chiefly on individual achievement, you don’t need to promote teamwork and should consider an individual incentive system. If success depends largely on cooperation among your direct reports and integration of their expertise, true teamwork is essential, and you should use group goals and incentives to gain alignment.

Usually, you will want to create incentives for both individual excellence (when your direct reports undertake independent tasks) and for team excellence (when they undertake interdependent tasks). The correct mix depends on the relative importance of independent and interdependent activity for the overall success of your unit. (See box, “The Incentive Equation.”) The Incentive Equation

The incentive equation defines the mix of incentives that you will use to motivate desired performance. Here are the basic formulas:

The relative sizes of nonmonetary and monetary rewards depend on (1) the availability of nonmonetary rewards such as advancement and recognition and (2) their perceived importance to the people involved.

The relative sizes of fixed and performance-based compensation depend on (1) the extent of observability and measurability of people’s contributions and (2) the time lag between performance and results. The lower the observability or measurability of contributions and the longer the time lag, the more you should rely on fixed compensation.

The relative sizes of individual and group-based performance compensation depend on the extent of interdependence of contributions. If superior performance comes from the sum of independent efforts, then individual performance should be rewarded (for example, in a sales group). If group cooperation and integration are critical, then group-based incentives should get more weight (for example, in a new-product development team). Note that there may be several levels of group-based incentives: team, unit, and company as a whole.

Designing incentive systems is a challenge, but the dangers of incentive misalignment are great. You need your direct reports to act as agents for you, whether they’re undertaking individual responsibilities or collective ones. You don’t want to give them incentives to pursue individual goals when true teamwork is necessary, or vice versa.

Articulate Your Vision

When you’re aligning your team, don’t forget about the organization’s vision. After all, it’s a key reason why you and your team come to work every day.

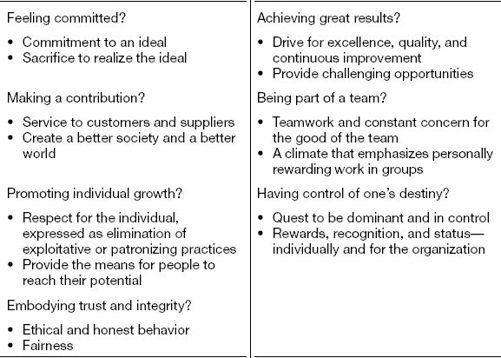

An inspiring vision has the following attributes:

It taps into sources of inspiration. It is built on a foundation of intrinsic motivators, such as teamwork and contribution to society. One orthopedic medical device company, for example, had “Restoring the joy of motion” as its vision statement, accompanied by stories about injured athletes being able to compete again, and grandparents being able to hold their grandkids.

It makes people part of “the story.” The best statements of vision connect people to a larger narrative that provides meaning—for example, a quest to recapture the organization’s past glories.

It contains evocative language. The vision must describe in graphic terms what the organization will achieve and how people will feel to have achieved it. Launching twelve rockets in ten years is a goal; putting a man on the moon and returning him safely to Earth by the end of the decade, as President John F. Kennedy put it, is a vision.

Use the categories in table 7-2 to help craft your shared vision. Keep asking yourself, Why should people feel inspired to expend extra effort to achieve the goals we have defined for the organization?

TABLE 7-2

Inspirations for vision statements

As you work to create and communicate a shared vision, keep the following principles in mind:

Use consultation to gain commitment. Be clear on which elements of your vision are nonnegotiable, but beyond these, be flexible enough to consider the ideas of others and allow them to have input and to influence the shared vision. In that way, they share ownership. Off-site meetings are often a powerful way to create and generate commitment to a shared vision, as long as you take care to ensure they are well designed. (See box, “Off-Site Planning Checklist.”) Develop stories and metaphors to communicate it. Stories and metaphors are potent ways to communicate the essence of a vision. There is something surprisingly powerful in a parable. The best of these stories crystallize core lessons and provide models for the kind of behavior you want to encourage.

Reinforce it. Research on persuasive communication heavily underlines the power of repetition. Your vision is more likely to take root in people’s minds if it consists of a few core themes that are repeated until they sink in. Even when people have begun to understand the message, you should not stop. Strive constantly to deepen people’s commitment to the vision.

Develop channels for communicating it. You cannot hope to communicate your vision directly to each person in your organization. This means that in addition to working with small groups such as a top team, you must be effective in persuading from a distance. This means developing communication channels that you will use to spread your vision more broadly.

Finally, and above all, take care to live the vision you articulate. A vision that is undercut by inconsistent leadership behaviors—by you or members of your team—is worse than no vision at all. Be sure you are prepared to walk the talk.

Off-Site Planning Checklist

Before you schedule an off-site meeting for your new team, you need to clarify the reasons for doing so. What are you trying to accomplish with this meeting? There are at least six important reasons for having off-site meetings: To gain a shared understanding of the business (diagnostic focus)

To define the vision and create a strategy (strategy focus)

To change the way the team works together (team-process focus)

To build or alter relationships in the group (relationship focus)

To develop a plan and commit to achieving it (planning focus)

To address conflicts and negotiate agreements (conflict-resolution focus)

Getting Down to Details

If you decide that an off-site meeting would indeed be useful for the group, start to consider the logistics of the meeting based on your answers to the following questions: When and where should the meeting be held?

Which issues will be dealt with, and in what order?

Who should act as facilitator?

Don’t neglect the facilitation question. If you are a skilled facilitator and if the team respects you—and is not enmeshed in a conflict—it may make sense for you to be both leader and facilitator. If not, you’d be well advised to bring in a skilled outsider—either an expert on the substance of the issues you’re dealing with or a skilled orchestrator of team process.

Avoiding the Traps

Don’t try to do too much in a single off-site meeting. You can’t realistically accomplish more than two of the goals outlined earlier in a day or two. Target a few, and stay focused.

Don’t put the cart before the horse. You can’t try to define the vision and create a strategy without first establishing the right foundation: a shared understanding of the business environment (diagnostic focus) and workplace relationships (relationship focus).

Leading Your Team

As you make progress in assessing, evolving, and aligning the team, think, too, about how you want to work with the team on a day-to-day, week-to-week basis. What processes will you use to shape how the team gets its collective job done? Teams vary strikingly in how they handle meetings, make decisions, resolve conflicts, and divide responsibilities and tasks. You will probably want to introduce new ways of doing things, but take care not to plunge into this task precipitously. First, familiarize yourself thoroughly with how your team worked before your arrival and how effective its processes were. In that way, you can preserve what worked well and change what did not.

Assess Your Team’s Existing Processes

How can you quickly get a handle on your team’s existing processes? Talk to team members, peers, and your boss about how the team worked. Read meeting minutes and team reports. Probe for answers to the following questions: Participants’ roles. Who exerted the most influence on key issues? Did anyone play devil’s advocate? Was there an innovator? Someone who avoided uncertainty? To whom did everyone else listen most attentively? Who was the peacemaker? The rabble-rouser?

Team meetings. How often did your team meet? Who participated? Who set the agendas for meetings?

Decision making. Who made what kinds of decisions? Who was consulted on decisions? Who was told after decisions were made?

Leadership style. What leadership style did your predecessor prefer? That is, how did he prefer to learn, communicate, motivate, and handle decisions? How does your predecessor’s leadership style compare with yours? If your styles differ markedly, how will you address the likely impact of those differences on your team?

Target Team Processes for Change

Once you grasp how your team functioned in the past—and what did and did not work well—use what you learn to establish the new processes you judge necessary. Many leaders decide, for example, that their team’s meeting and decision-making processes would benefit from revision. If this is true of you, begin spelling out in specific terms what changes you envision. How often will the team meet? Who will attend which meetings? How will agendas be established and circulated? Setting up clear and effective processes will help your team coalesce and secure some early wins as a group.

Alter the Participants

One common team dysfunction—and a great opportunity to send a message that change is coming—concerns who participates in core team meetings. In some organizations, key meetings are too inclusive, with too many people participating in discussions and decision making. If this is the case, then reduce the size of the core group and streamline the meetings, sending the message that you value efficiency and focus. In other organizations, key meetings are too exclusive, with people who have potentially important opinions and information being systematically excluded. If this is the case, then judiciously broaden participation, sending the message that you will not play favorites or listen to only a few points of view.

Lead Decision Making

Decision making is another fertile area for potential improvement. Few leaders do a great job of leading team decision making. In part, this is because different types of decisions call for different decision-making processes, but most team leaders stick with one approach. They do this because they have a style with which they are comfortable and because they believe they need to be consistent or risk confusing their direct reports.

Research suggests that this view is wrongheaded.3 The key is to have a framework for understanding and communicating why different decisions will be approached in different ways.

Think of the different ways teams can make decisions. Possible approaches can be arrayed on a spectrum ranging from unilateral decision making at one end to unanimous consent at the other. In unilateral decision making, the leader simply makes the call, either without consultation or with limited consultation with personal advisers. The risks associated with this approach are obvious: you may miss critical information and insights and get only lukewarm support for implementation.

At the other extreme, processes that require unanimous consent from more than a few people tend to suffer from decision diffusion. They go on and on, never reaching closure. Or, if a decision does get made, it is often a lowest-common-denominator compromise. In either case, critical opportunities and threats are not addressed effectively.

Between these two extremes are the decision-making processes that most leaders use: consult-and-decide and build consensus. When a leader solicits information and advice from direct reports—individually, as a group, or both—but reserves the right to make the final call, she is using a consult-and-decide approach. In effect she separates the “information gathering and analysis” process from the “evaluating and reaching closure” process, harnessing the group for one but not the other.

In the build-consensus process, the leader both seeks information and analysis and seeks buy-in from the group for any decision. The goal is not full consensus but sufficient consensus. This means that a critical mass of the group believes the decision to be the right one and, critically, that the rest agree they can live with and support implementation of the decision.

When should you choose one process over the other? The answer is emphatically not “If I am under time pressure, I will use consult-and-decide.” Why? Because even though you may reach a decision more quickly by the consult-and-decide route, you won’t necessarily reach the desired outcome faster. In fact, you may end up consuming a lot of time trying to sell the decision after the fact, or finding out that people are not energetically implementing it and having to pressure them. Those who suffer from the action imperative are most at risk of this; they want to reach closure by making the call but may jeopardize their end goals in the process.

The following rules of thumb can help you figure out which decision-making process to use:

If the decision is likely to be highly divisive—creating winners and losers—then you usually are better off using consult-and-decide and taking the heat. A build-consensus process will fail to reach a good outcome and will get everyone mad at one another in the process. Put another way, decisions about sharing losses or pain among a group of people are best made by the leader.

If the decision requires energetic support for implementation from people whose performance you cannot adequately observe and control, then you usually are better off using a build-consensus process. You may get to a decision more quickly using consult-and-decide, but you may not get the desired outcome.

If your team members are inexperienced, then you usually are better off relying more on consult-and-decide until you’ve taken the measure of the team and developed their capabilities. If you try to adopt a build-consensus approach with an inexperienced team, you risk getting frustrated and imposing a decision anyway, and that undercuts teamwork.

If you’re put in charge of a group with whom you need to establish your authority (such as supervising former peers), then you’re better off relying on consult-and-decide to make some key early decisions. You can relax and rely more on building consensus once people see that you have the steadiness and insight to make tough calls.

Your approach to decision making will also vary depending on which of the STARS situations you’re in. In start-ups and turnarounds, consult-and-decide often works well. The problems tend to be technical (markets, products, technologies) rather than cultural and political. Also, people may be hungry for “strong” leadership, which often is associated with a consult-and-decide style. To be effective in realignment and sustaining-success situations, in contrast, leaders often need to deal with strong, intact teams and confront cultural and political issues. These sorts of issues are typically best addressed with the build-consensus approach.

To alter your approach to decision making depending on the nature of the decision to be made, you will sometimes have to restrain your natural inclinations. You are likely to have a preference for either consult-and-decide or build-consensus decision making. But preferences are not destiny. If you are a consult-and-decide person, you should consider experimenting with building (sufficient) consensus in suitable situations. If you are a build-consensus person, you should feel free to adopt a consult-and-decide approach when it is appropriate to do so.

To avoid confusion, consider explaining to your direct reports what process you’re using and why. More importantly, strive to run a fair process.4 Even if people do not agree with the final decision, they often will support it if they feel (1) that their views and interests have been heard and taken seriously and (2) that you have given them a plausible rationale for why you made the call you did. The corollary? Don’t engage in a charade of consensus building—an effort to build support for a decision already made. This rarely fools anyone, and it creates cynicism and undercuts implementation. You are better off to simply use consult-and-decide.

Finally, you often can shift between build-consensus and consult-and-decide modes as you gain deeper insight into peoples’ interests and positions. It may make sense, for example, to begin in a consensus-building mode but reserve the right to shift to consult-and-decide if the process is becoming too divisive. It also may make sense to begin with consult-and-decide and shift to build-consensus if it emerges that energetic implementation is critical and consensus is possible.

Adjust for Virtual Teams

Finally, how should you modify your approach to building your team if some or all of the members are working remotely? It’s a big challenge to gain and sustain cohesion in virtual teams. It also makes it more difficult to evaluate team members, especially if the situation precludes early face-to-face meetings. Although most of the principles of effective teamwork apply to virtual teams, there are a few additional things to consider: Bring the team together early if at all possible. The technology to support virtual interactions is improving. However, if true teamwork is required, there still is no substitute for getting people together to establish a shared foundation of knowledge, relationships, alignment, and mutual commitment.

Establish clear norms about communication. This includes which communication channels will be used and how they will be employed. It also means having explicit agreements concerning responsiveness—for example, that urgent messages will be responded to within a specified time. Often it’s essential as well to have clear norms about how people will interact during virtual meetings—for example, interrupting less than usual when meeting face-to-face, but also being more efficient in putting points across.

Clearly define team support roles. Virtual teams need to be more disciplined about capturing and sharing information as well as following up on commitments. It often helps to assign people specific team support roles (perhaps on a rotating basis), such as note-taker and agenda-creator.

Create a rhythm for team interaction. Co-located teams naturally establish patterns and routines for interaction; these can be as simple as arriving at roughly the same time or talking over coffee. Virtual teams, especially those working in multiple time zones, lack natural opportunities to create these reassuring routines. Therefore, it’s essential to provide a lot of structure for virtual team interaction—for example, setting meeting times and following specified agendas.

Don’t forget to celebrate success. It’s easy for members of a virtual team to feel disconnected, especially if most of the team is co-located and only a few are working remotely. Although it’s always important to pause occasionally to recognize and celebrate accomplishments, it’s essential in virtual teams.

Jump-Starting the Team

Your decisions about the team you inherited probably will be the most important decisions you make. Done well, your effort to assess, evolve, align, and lead the team will pay dividends in the focus and energy people bring to achieving goals and securing early wins. You will know you’ve been successful in building your team when you reach the break-even point—when the energy the team creates is greater than the energy you need to put into it. It will take a while before that happens; you must charge the battery before you can start the engine.

BUILD YOUR TEAM—CHECKLIST

What are your criteria for assessing the performance of members of your team? How are relative weightings affected by functions, the extent of required teamwork, the STARS portfolio, and the criticality of the positions?

How will you go about assessing your team?

What personnel changes do you need to make? Which changes are urgent, and which can wait? How will you create backups and options?

How will you make high-priority changes? What can you do to preserve the dignity of the people affected? What help will you need with the team in the restructuring process, and where are you going to find it?

How will you align the team? What mix of push (goals, incentives) and pull (shared vision) will you use?

How do you want your new team to operate? What roles do you want people to play? Do you need to shrink the core team or expand it? How do you plan to manage decision making?

مشارکت کنندگان در این صفحه

تا کنون فردی در بازسازی این صفحه مشارکت نداشته است.

🖊 شما نیز میتوانید برای مشارکت در ترجمهی این صفحه یا اصلاح متن انگلیسی، به این لینک مراجعه بفرمایید.