سرفصل های مهم

فصل پنجم : درباره موفقیت مذاکره کنید

توضیح مختصر

- زمان مطالعه 0 دقیقه

- سطح خیلی سخت

دانلود اپلیکیشن «زیبوک»

فایل صوتی

برای دسترسی به این محتوا بایستی اپلیکیشن زبانشناس را نصب کنید.

ترجمهی فصل

متن انگلیسی فصل

CHAPTER 5

Secure Early Wins

When Elena Lee was promoted to head customer service at a leading retailer, she was tasked with improving slumping customer satisfaction. She also was determined to change the authoritarian leadership culture exemplified by her predecessor. Before her promotion, Elena had been responsible for the highest-performing call center in the same organization, so she knew a lot about the problems other units had been facing with quality of service. Convinced that she could dramatically improve performance through more employee participation, she saw cultural change as a top priority.

Elena began by communicating her goals to her former peers, now direct reports—the leaders of the company’s call centers across the globe. In a series of team calls and 1:1 meetings, she laid out her quality improvement goals and vision for a more participative, problem-solving culture. These early overtures generated little obvious reaction.

Next, she initiated weekly meetings with each of the call center managers to review unit performance and discuss how they were working to improve it. Elena stressed that “the punishment culture is a thing of the past” and that she expected managers to coach employees. Cases involving significant disciplinary measures, she said, should be referred (on an interim basis) directly to her for review.

Over time Elena learned which center managers were getting with the program and which ones were continuing to be punitive. She then conducted formal performance reviews and put two of the worst offenders on performance-improvement plans. One left almost immediately; she replaced him with a high-potential supervisor from the center she had run. Although it took some time, the other manager shaped up acceptably.

Meanwhile, Elena focused on a critical aspect of the business: evaluation of customer satisfaction and improvement in quality of service. She appointed her best unit leader to lead a team of promising frontline managers and tasked them with producing a plan to introduce new metrics and supporting performance feedback and improvement processes. She also engaged a consultant to advise the managers on how to pursue this project, and she regularly reviewed their progress. When the team presented recommendations, she promptly implemented them on a pilot basis in the unit previously overseen by the departed supervisor.

By the end of her first year, Elena had extended the new approach throughout the organization. Customer service had improved substantially, and climate surveys revealed striking improvements in morale and employee satisfaction.

Elena succeeded in quickly creating momentum and building personal credibility by securing early wins.1 By the end of the first few months, you want your boss, your peers, and your subordinates to feel that something new, something good, is happening. Early wins excite and energize people and build your personal credibility. Done well, they help you create value for your new organization earlier and reach the break-even point much more quickly.

Making Waves

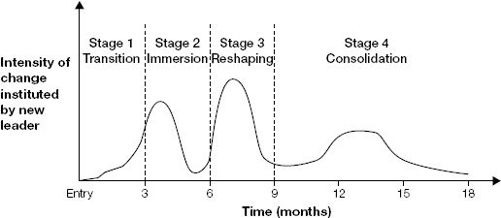

A seminal study of executives in transition found that they plan and implement change in distinct waves, as illustrated in figure 5-1.2 Following an early period of focused learning, these leaders begin an early wave of changes. The pace then slows to allow consolidation and deeper learning about the organization, and to allow people to catch their breath. Armed with more insight, these executives then implement deeper waves of change. A final, less extreme wave focuses on fine-tuning to maximize performance. By this point, most of these leaders are ready to move on.

This research has direct implications for how you should manage your transition. It suggests that you should keep your ends clearly in mind when you devise your plan to secure early wins. The transition lasts only a few months, but you typically will remain in the same job for two to four years before moving on to a new position. To the greatest extent possible, your early wins should advance longer-term goals.

Waves of change

Plan Your Waves

In planning for your transition (and beyond), focus on making successive waves of change. Each wave should consist of distinct phases: learning, designing the changes, building support, implementing the changes, and observing results. Thinking in this way can release you to spend time up front to learn and prepare, and afterward to consolidate and get ready for the next wave. If you keep changing things, it is impossible to figure out what is working and what is not. Unending change is also a surefire recipe for burning out your people.

The goal of the first wave of change is to secure early wins. The new leader tailors early initiatives to build personal credibility, establish key relationships, and identify and harvest low-hanging fruit—the highest-potential opportunities for short-term improvements in organizational performance. Done well, this strategy helps the new leader build momentum and deepen his own learning.

The second wave of change typically addresses more fundamental issues of strategy, structure, systems, and skills to reshape the organization; deeper gains in organizational performance are achieved. But you will not get there if you don’t secure early wins in the first wave.

Starting with the Goal

Leaders in transition understandably are eager to get things moving. Thus, they naturally tend to focus on the problems that are easiest to fix quickly. This tactic is fine, up to a point. But be careful not to fall into the low-hanging fruit trap. This trap catches leaders when they expend most of their energy seeking early wins that don’t contribute to achieving their longer-term business objectives. It’s like trying to launch a rocket into orbit with nothing except a very big first stage; the risk is great that you’ll fall back to earth once the initial momentum fades. The implication: when you’re deciding where to seek early wins, you may have to forgo some of the low-hanging fruit and reach higher in the tree.

As you strive to create momentum, therefore, keep in mind that your early wins must do double duty: they must help you build momentum in the short term and lay a foundation for achieving your longer-term business goals. So be sure that your plans for securing early wins, to the greatest extent possible, (1) are consistent with your agreed-to goals—what your bosses and key stakeholders expect you to achieve—and (2) help you introduce the new patterns of behavior you need to achieve those goals.

Focus on Business Priorities

The goals you have agreed to with your boss and other key stakeholders are the destination you’re striving to reach in measurable business objectives. Examples are double-digit annual profit growth; a dramatic cut in defects and rework; or completion of a key project by an agreed-to deadline. For Elena, her number 1 priority was to make significant improvements in customer satisfaction. The point is to define your goals so that you can lead with a distinct end point in mind.

Identify and Support Behavioral Changes

Your agreed-to goals are the destination, but the behavior of people in your organization is a key part of how you do (or don’t) get there. Put another way, if you are to achieve your goals in the allotted time, you may have to change dysfunctional patterns of behavior.

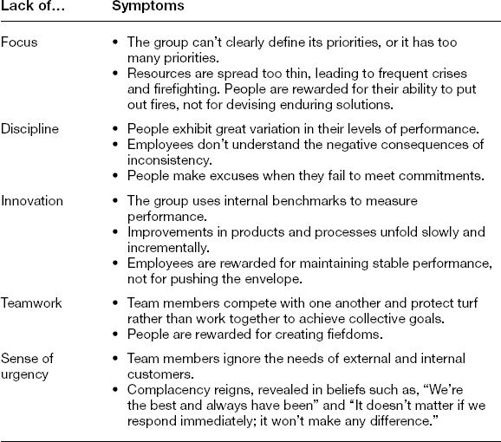

Start by identifying the unwanted behaviors; for example, Elena wanted to reduce the fear and disempowerment in her organization. Then work out, as Elena did, a clear vision of how you would like people to behave by the end of your tenure in the job, and plan how your actions in pursuit of early wins will advance the process. What behaviors do people consistently display that undermine the potential for high performance? Take a look at table 5-1, which lists some problematic behavior patterns, and then summarize your thoughts about the behaviors you would like to change.

Problematic behavior patterns

Adopting Basic Principles

It’s crucial to get early wins, but it’s also important to secure them in the right way. Above all, of course, you want to avoid early losses, because it’s tough to recover once the tide is running against you. Here are some basic principles to consider.

Focus on a few promising opportunities. It’s easy to take on too much during a transition, and the results can be ruinous. You cannot hope to achieve results in more than a couple of areas during your transition. Thus, it’s essential to identify the most promising opportunities and then focus relentlessly on translating them into wins. Think of it as risk management: pursue enough focal points to have a good shot at getting a significant success, but not so many that your efforts get diffused.

Get wins that matter to your boss. It’s essential to get early wins that energize your direct reports and other employees. But your boss’s opinion about your accomplishments is crucial too. Even if you do not fully endorse her priorities, you must make them central in thinking through which early wins you will aim for. Addressing problems that your boss cares about will go a long way toward building credibility and cementing your access to resources.

Get wins in the right ways. If you achieve impressive results in a manner that is seen as manipulative, underhanded, or inconsistent with the culture, you’re setting yourself up for trouble. If Elena had gotten her key wins by being punitive, it would have undercut the larger objective she was trying to achieve. An early win that is accomplished in a way that exemplifies the behavior you hope to instill in your new organization is a double win.

Take your STARS portfolio into account. What constitutes an early win differs dramatically from one STARS business situation to another. Simply getting people to talk about the organization and its challenges can be a big accomplishment in a realignment, but it’s a waste of time in a turnaround. So think hard about what will build momentum best in each part of your portfolio. Will it be a demonstrated willingness to listen and learn? Will it be rapid, decisive calls on pressing business issues?

Adjust for the culture. In some organizations, a win must be a visible individual accomplishment. In others, individual pursuit of glory, even if it achieves good results, is viewed as grandstanding and destructive of teamwork. In team-oriented organizations, early wins could come in the form of leading a team in the development of a new product idea or being viewed as a solid contributor and team player in a broader initiative. Be sure you understand what is and is not viewed as a win, especially if you’re onboarding into the organization.

Identifying Your Early Wins

Armed with (and guided by) an understanding of your goals and objectives for behavior change, you can identify where you will seek early wins. You should think about what you need to do in two phases: building personal credibility in roughly the first 30 days, and deciding which projects you will launch to achieve early performance improvements beyond that. (The actual time frames will of course depend on the situation.) Understand Your Reputation

When you arrive, people will rapidly begin to assess you and your capabilities. In part, this evaluation will be based on what people think they already “know” about you. You can be sure people have talked to people who have talked to people who have worked with you in the past. So like it or not, you will start your role with a reputation, deserved or not. The risk, of course, is that your reputation will become reality, because people tend to focus on information that confirms their beliefs and screen out information that doesn’t—the so-called confirmation bias.3 The implication is that you need to figure out what role people are expecting you to play and then make an explicit decision about whether you will reinforce these expectations or confound them.

Elena’s situation—leading former peers—is a special case in which people in the organization knew her, but in a different, more junior role. The risk for her was that they would expect her to be the same in her new role. So her job was to figure out ways to change how people perceived her. The broader challenges of leading former peers are summarized in the box “Leading Former Peers.” Leading Former Peers

To meet the classic challenges of moving from peer to boss, you should adopt the following principles:

Accept the fact that relationships must change. An unfortunate price of promotion is that personal relationships with former peers must become less so. Close personal relationships are rarely compatible with effective supervisory ones.

Focus early on rites of passage. The first days are about symbolism more than substance. So focus on rites of passage can help establish you in your new role—for example, having your new boss introduce you to your team and pass the baton.

Reenlist your (good) former peers. For every leader who gets promoted, there are other ambitious souls who wanted the job but didn’t get it. So recognize that disappointed competitors will go through stages of adjustment. Focus on figuring out who can work for you and who can’t.

Establish your authority deftly. You must walk the knife’s edge between over- and underasserting yourself. It can be effective to adopt a consult-and-decide approach when dealing with critical issues until former peers get used to making the calls, as long as you don’t make uninformed decisions.

Focus on what’s good for the business. From the moment your appointment is announced, some former peers will be straining to discern whether you will play favorites or will seek to advance political agendas at their expense. One antidote is to adopt a relentless, principled focus on doing what is right for the business.

Build Credibility

In your first few weeks in your new job, you cannot hope to have a measurable impact on performance, but you can score small victories and signal that things are changing. Think of this as an effort to secure early, early wins by building your personal credibility.

Your credibility, or lack of it, will depend on how people would answer the following questions about you:

Do you have the insight and steadiness to make tough decisions?

Do you have values that they relate to, admire, and want to emulate?

Do you have the right kind of energy?

Do you demand high levels of performance from yourself and others?

For better or worse, they will begin to form opinions based on little data. Your early actions, good and bad, will shape perceptions. Once opinion about you has begun to harden, it is difficult to change. And the opinion-forming process happens remarkably quickly.

So how do you build personal credibility? In part, it’s about marketing yourself effectively, much akin to building equity in a brand. You want people to associate you with attractive capabilities, attitudes, and values. There’s no single right answer for how to do this. In general, though, new leaders are perceived as more credible when they display these characteristics: Demanding but able to be satisfied. Effective leaders get people to make realistic commitments and then hold them responsible for achieving results. But if you’re never satisfied, you’ll sap people’s motivation. Know when to celebrate success and when to push for more.

Accessible but not too familiar. Being accessible does not mean making yourself available indiscriminately. It means being approachable, but in a way that preserves your authority.

Decisive but judicious. New leaders communicate their capacity to take charge, perhaps by rapidly making some low-consequence decisions, without jumping too quickly into decisions that they aren’t ready to make. Early in your transition, you want to project decisiveness but defer some decisions until you know enough to make the right calls.

Focused but flexible. Avoid setting up a vicious cycle and alienating others by coming across as rigid and unwilling to consider multiple solutions. Effective new leaders establish authority by zeroing in on issues but consulting others and encouraging input. They also know when to give people the flexibility to achieve results in their own ways.

Active without causing commotion. There’s a fine line between building momentum and overwhelming your group or unit. Make things happen, but avoid pushing people to the point of burnout. Learn to pay attention to stress levels and pace yourself and others.

Willing to make tough calls but humane. You may have to make tough calls right away, including letting go of marginal performers. Effective new leaders do what needs to be done, but they do it in ways that preserve people’s dignity and that others perceive as fair. Keep in mind that people watch not only what you do but also how you do it.

Plan to Engage

Because your earliest actions will have a disproportionate influence on how you’re perceived, think through how you will get connected to your new organization in the first few days in your new role. What messages do you want to get across about who you are and what you represent as a leader? What are the best ways to convey those messages? Identify your key audiences—direct reports, other employees, key outside constituencies—and craft a few messages tailored to each. These need not be about what you plan to do; that’s premature. They should focus instead on who you are, the values and goals you represent, your style, and how you plan to conduct business.

Think about modes of engagement, too. How will you introduce yourself? Should your first meetings with direct reports be one-on-one or in a group? Will these meetings be informal get-to-know-you sessions, or will they immediately focus on business issues and assessment? What other channels, such as e-mail and video, will you use to introduce yourself more widely? Will you have early meetings at other locations where your organization has facilities?

As you make progress in getting connected, identify and act as quickly as you can to remove minor but persistent irritants. Focus on strained external relationships, and begin to repair them. Cut out redundant meetings, shorten excessively long ones, or improve problems with physical work spaces. All this helps you build personal credibility early on.

Finally, keep in mind that effective learning builds personal credibility. It’s never a bad thing to be seen as genuinely committed to understanding your new organization. It helps immunize you against the perception that you have come in with your mind made up about the organization’s problems and have “the” answer. An early, visible focus on learning signals to the organization that you understand it has a unique history and dynamics. Of course, it’s important that you also be seen as a quick study and not, as was said of one president, that you have “a learning curve as flat as Kansas.”4 Know, too, when to shift the emphasis from learning to decision and action.

Write Your Own Story

Your actions during your first few weeks inevitably will have a disproportionate impact, because they are as much about symbolism as about substance. Early actions often get transformed into stories, which can define you as hero or villain. Do you take the time to informally introduce yourself to the support staff, or do you focus only on your boss, peers, and direct reports? Something as simple as this action can help brand you as either accessible or remote. How you introduce yourself to the organization, how you treat support staff, how you deal with small irritants—all these pieces of behavior can become the kernels of stories that circulate widely.

To nudge your mythology in a positive direction, look for and leverage teachable moments. These are actions—such as the way Elena dealt with recalcitrant supervisors—that clearly display what you’re about; they also model the kinds of behavior you want to encourage. They need not be dramatic statements or confrontations. They can be as simple, and as hard, as asking the penetrating question that crystallizes your group’s understanding of a key problem the members are confronting.

Launch Early-Win Projects

Building personal credibility and developing some key relationships help you get immediate wins. Soon, however, you should identify opportunities to get quick, tangible performance improvement in the business. The best candidates are problems you can tackle quickly with modest expenditures and will yield visible operational and financial gains. Examples include bottlenecks that restrict productivity and incentive programs that undermine performance by causing conflict.

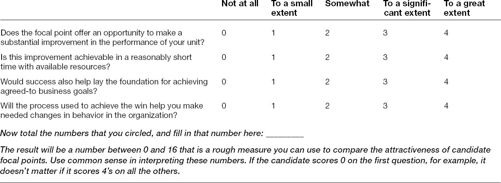

Identify three or four key areas, at most, where you will seek to achieve rapid improvement. Use the early wins evaluation tool in table 5-2 to gauge the potential. But keep in mind that if you take on too many initiatives, you risk losing focus. Think about risk management: build a promising portfolio of early-win initiatives so that big successes in one will balance disappointments in others. Then focus relentlessly on getting results.

Early wins evaluation tool

This tool helps you assess the potential of candidate focal points for getting early wins. Complete one for each candidate focal point, carefully answering the evaluation questions. Then total the scores for the evaluation question, and use the result as a rough indicator of the potential.

CANDIDATE EARLY WIN __________________

For each of the following questions, circle the response that best describes the potential.

To set the stage for securing early wins, make sure your learning agenda specifically addresses how you will identify promising opportunities for improvement. Then translate your goals into specific projects to secure early wins, using the following guidelines: Keep your long-term goals in mind. Your actions should, to the greatest extent possible, serve your agreed-to business goals and supporting objectives for behavior change.

Identify a few promising focal points. Focal points are areas or processes (such as the customer service processes for Elena) in which improvement can dramatically strengthen the organization’s overall operational or financial performance. Concentration on a few focal points will help you reduce the time and energy needed to achieve tangible results. And success in improving performance early in these areas will win you freedom and space to pursue more extensive changes.

Launch early-win projects. Manage your early-win initiatives as projects, targeted at your chosen focal points. This is what Elena did when she appointed a team to improve customer service in her new position.

Elevate change agents. Identify the people in your new unit, at all levels, who have the insight, drive, and incentives to advance your agenda. Promote them or appoint them to lead key projects, as Elena did.

Leverage the early-win projects to introduce new behaviors. Your early-win projects should serve as models of how you want your organization, unit, or group to function in the future. Elena understood this when she engaged a consultant to help the team use the right methods to pursue the project so they could learn how best to do this.

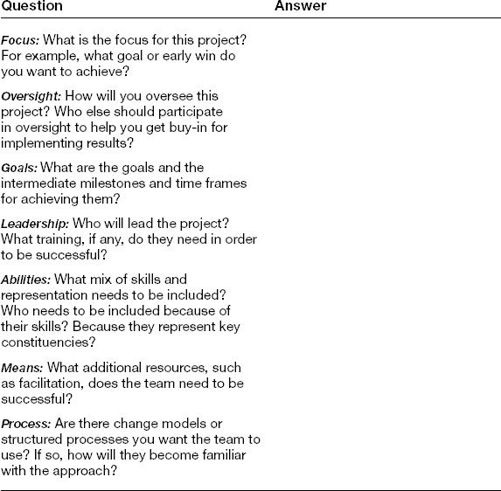

Use the project planning template in table 5-3 to plan projects with maximum impact.

FOGLAMP project checklist

FOGLAMP is an acronym for focus, oversight, goals, leadership, abilities, means, and process. This tool can help you cut through the haze and plan your critical projects. Complete the table for each early-win project you set up.

Project: __________

Leading Change

As you work out where to get your early wins, think, too, about how you will make change happen in your organization. Keep in mind there is no one best way to lead change; the best approaches depend on the situation. For example, approaches that work well in turnarounds, where there already is a sense of urgency, can fail miserably in realignments, where many people may be in denial about the need for change. So stay open to the possibility that you will lead change differently in different parts of your STARS portfolio.

Planning Versus Learning

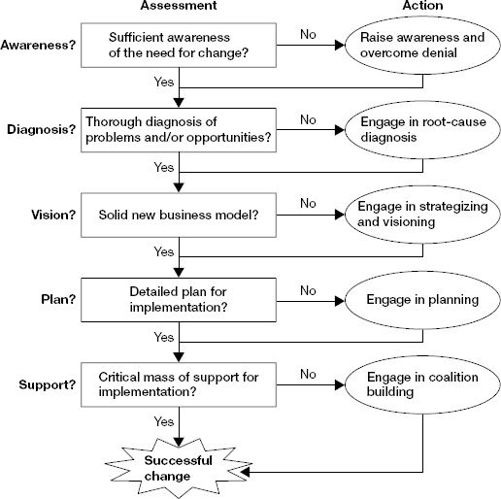

Once you’ve identified the most important problems or issues you need to address, the next step is to decide whether to engage in planned change or collective learning.5 The straightforward plan-then-implement approach to change works well when you’re sure you have the following key supporting planks in place:

Awareness. A critical mass of people is aware of the need for change.

Diagnosis. You know what needs to be changed and why.

Vision. You have a compelling vision and a solid strategy.

Plan. You have the expertise to put together a detailed plan.

Support. You have sufficiently powerful alliances to support implementation.

This approach often works well in turnaround situations—for example, where people accept there is a problem, the fixes are more technical than cultural or political, and people are hungry for a solution.

If any of these five conditions is not met, however, the pure planning approach to change can get you into trouble. If you’re in a realignment, for example, and people are in denial about the need for change, they’re likely to greet your plan with stony silence or active resistance. You may therefore need to build awareness of the need for change. Or you may need to sharpen the diagnosis of the problem, create a compelling vision and strategy, develop a solid cross-functional implementation plan, or create a coalition in support of change.

To accomplish any of these goals, you would be well advised to focus on setting up a collective learning process and not on developing and imposing change plans. If many people in the organization are willfully blind to emerging problems, for example, you must put in place a process to pierce this veil. Rather than mount a frontal assault on the organization’s defenses, you should engage in something akin to guerrilla warfare, slowly chipping away at people’s resistance and raising their awareness of the need for change.

You can do this by exposing key people to new ways of operating and thinking about the business, such as new data on customer satisfaction and competitive offerings. Or you can do some benchmarking of best-in-class organizations, getting the group to analyze how your best competitors perform. Or you can persuade people to envision new approaches to doing things—for example, by scheduling an off-site meeting to brainstorm about key objectives or ways to improve existing processes.

The key, then, is to figure out which parts of the change process can be best addressed through planning, and which are better dealt with through collective learning. Think of a change you want to make in your new organization. Now use the diagnostic flow chart in figure 5-2 to figure out where planning and learning processes are likely to be important to your success.

Diagnostic framework for managing change

Get Started on Behavior Change

As you plan to get early wins, remember that the means you use are as important as the ends you achieve. The initiatives you put in place to get early wins should do double duty by establishing new standards of behavior. Elena did this when she carefully staffed and coached her project team and then quickly implemented its recommendations.

To change your organization, you will likely have to change its culture. This is a difficult undertaking. Your organization may have well-ingrained bad habits that you want to break. But we know how difficult it is for one person to change habitual patterns in any significant way, never mind a mutually reinforcing collection of people.

Simply blowing up the existing culture and starting over is rarely the right answer. People—and organizations—have limits on the change they can absorb all at once. And organizational cultures invariably have virtues as well as faults; they provide predictability and can be sources of pride. If you send the message that there is nothing good about the existing organization and its culture, you will rob people of a key source of stability in times of change. You also will deprive yourself of a potential wellspring of energy you could tap to improve performance.

The key is to identify both the good and the bad elements of the existing culture. Elevate and praise the good elements even as you seek to change the bad ones. These functional aspects of the familiar culture are a bridge that can help carry people from the past to the future.

Match Strategy to Situation

The choice of behavior-change techniques should be a function of your group’s structure, processes, skills, and—above all—situation. Consider again the difference between turnaround and realignment situations. In a turnaround, you face a combination of time pressure and the need to rapidly identify and secure the defensible core of the business. Often, techniques such as bringing in new people from the outside and setting up project teams to pursue specific performance-improvement initiatives are a good fit. Contrast this with realignments, where you are well advised to start with less obvious approaches to behavior change. By changing performance measures and starting benchmarking, for example, you set the stage for collectively creating a vision for realigning the business.

Avoiding Predictable Surprises

Finally, all your efforts to secure early wins could come to naught if you don’t pay attention to identifying ticking time bombs and preventing them from exploding in your face. If they do explode, your focus will instantly shift to continuous firefighting, and your hopes for systematically getting established and building momentum will fly out the window.

Some bolts from the blue really do come out of the blue. When this happens, you must grit your teeth and mount the best crisis response you can. But far more often, new leaders are taken off track by predictable surprises. These are situations in which people have all the information necessary to recognize and defuse a time bomb but fail to do so.6 This often happens because the new leader simply doesn’t look in the right places or ask the right questions. As mentioned earlier, we all have preferences about the types of problems we like to work on and those we prefer to avoid or don’t feel competent to address. But you need to discipline yourself either to dig into areas where you’re not fully comfortable or to find trustworthy people with the necessary expertise to do so.

Another reason for predictable surprises is that different parts of the organization have different pieces of the puzzle, but no one puts them together. Every organization has its information silos. If you don’t put processes in place to make sure critical information is surfaced and integrated, then you’re putting yourself at risk of being predictably surprised.

Use the following set of questions to identify areas where potential problems may be lurking:

The external environment. Could trends in public opinion, government action, or economic conditions precipitate major problems for your unit? Examples include a change in government policy that favors competitors or unfavorably influences your prices or costs; a major shift in public opinion about the health or safety implications of using your product; an emerging economic crisis in a developing country.

Customers, markets, competitors, and strategy. Are there developments in the competitive situation confronting your organization that could pose major challenges? Examples include a study suggesting that your product is inferior to that of a competitor; a new competitor that is offering a lower-cost substitute; a price war.

Internal capabilities. Are there potential problems with your unit’s processes, skills, and capabilities that could precipitate a crisis? Examples include an unexpected loss of key personnel; major quality problems at a key plant; a product recall.

Organizational politics. Are you in danger of unwittingly stepping on a political land mine? Examples include certain people in your unit who are untouchable, but you don’t know it; your failure to recognize that a key peer is subtly undermining you.

As you plan how to secure early wins, keep in mind your overarching goal: creating a virtuous cycle that reinforces wanted behavior and contributes to helping you achieve your agreed-to goals for the organization. Remember that you’re aiming at modest but significant early improvements so that you can pursue more fundamental changes.

Secure Early Wins—Checklist

Given your agreed-to business goals, what do you need to do during your transition to create momentum for achieving them?

How do people need to behave differently to achieve these goals? Describe as vividly as you can the behaviors you need to encourage and those you need to discourage.

How do you plan to connect yourself to your new organization? Who are your key audiences, and what messages would you like to convey to them? What are the best modes of engagement?

What are the most promising focal points to get some early improvements in performance and start the process of behavior change?

What projects do you need to launch, and who will lead them?

What predictable surprises could take you off track?

مشارکت کنندگان در این صفحه

تا کنون فردی در بازسازی این صفحه مشارکت نداشته است.

🖊 شما نیز میتوانید برای مشارکت در ترجمهی این صفحه یا اصلاح متن انگلیسی، به این لینک مراجعه بفرمایید.