سرفصل های مهم

فصل 5

توضیح مختصر

- زمان مطالعه 0 دقیقه

- سطح خیلی سخت

دانلود اپلیکیشن «زیبوک»

فایل صوتی

برای دسترسی به این محتوا بایستی اپلیکیشن زبانشناس را نصب کنید.

ترجمهی فصل

متن انگلیسی فصل

Chapter 5

LAST MOVER ADVANTAGE

ESCAPING COMPETITION will give you a monopoly, but even a monopoly is only a great business if it can endure in the future. Compare the value of the New York Times Company with Twitter. Each employs a few thousand people, and each gives millions of people a way to get news. But when Twitter went public in 2013, it was valued at $24 billion—more than 12 times the Times’s market capitalization—even though the Times earned $133 million in 2012 while Twitter lost money. What explains the huge premium for Twitter?

The answer is cash flow. This sounds bizarre at first, since the Times was profitable while Twitter wasn’t. But a great business is defined by its ability to generate cash flows in the future. Investors expect Twitter will be able to capture monopoly profits over the next decade, while newspapers’ monopoly days are over.

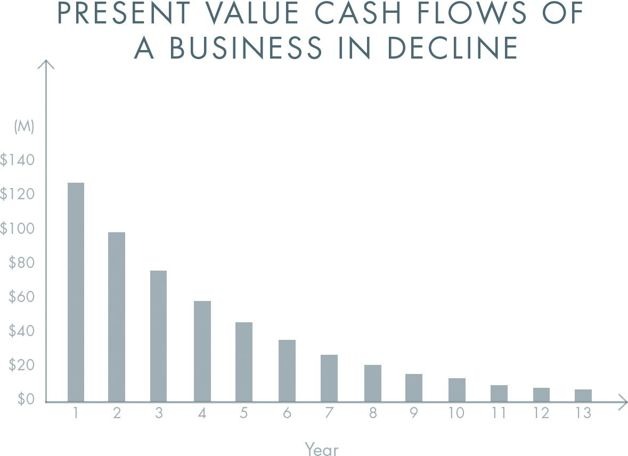

Simply stated, the value of a business today is the sum of all the money it will make in the future. (To properly value a business, you also have to discount those future cash flows to their present worth, since a given amount of money today is worth more than the same amount in the future.) Comparing discounted cash flows shows the difference between low-growth businesses and high-growth startups at its starkest. Most of the value of low-growth businesses is in the near term. An Old Economy business (like a newspaper) might hold its value if it can maintain its current cash flows for five or six years. However, any firm with close substitutes will see its profits competed away. Nightclubs or restaurants are extreme examples: successful ones might collect healthy amounts today, but their cash flows will probably dwindle over the next few years when customers move on to newer and trendier alternatives.

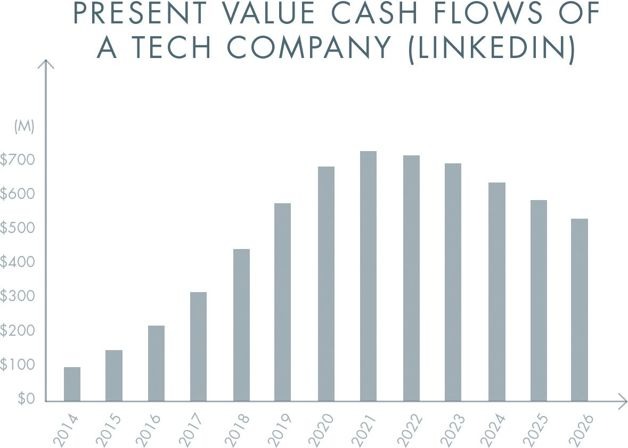

Technology companies follow the opposite trajectory. They often lose money for the first few years: it takes time to build valuable things, and that means delayed revenue. Most of a tech company’s value will come at least 10 to 15 years in the future.

In March 2001, PayPal had yet to make a profit but our revenues were growing 100% year-over-year. When I projected our future cash flows, I found that 75% of the company’s present value would come from profits generated in 2011 and beyond—hard to believe for a company that had been in business for only 27 months. But even that turned out to be an underestimation. Today, PayPal continues to grow at about 15% annually, and the discount rate is lower than a decade ago. It now appears that most of the company’s value will come from 2020 and beyond.

LinkedIn is another good example of a company whose value exists in the far future. As of early 2014, its market capitalization was $24.5 billion—very high for a company with less than $1 billion in revenue and only $21.6 million in net income for 2012. You might look at these numbers and conclude that investors have gone insane. But this valuation makes sense when you consider LinkedIn’s projected future cash flows.

The overwhelming importance of future profits is counterintuitive even in Silicon Valley. For a company to be valuable it must grow and endure, but many entrepreneurs focus only on short-term growth. They have an excuse: growth is easy to measure, but durability isn’t. Those who succumb to measurement mania obsess about weekly active user statistics, monthly revenue targets, and quarterly earnings reports. However, you can hit those numbers and still overlook deeper, harder-to-measure problems that threaten the durability of your business.

For example, rapid short-term growth at both Zynga and Groupon distracted managers and investors from long-term challenges. Zynga scored early wins with games like Farmville and claimed to have a “psychometric engine” to rigorously gauge the appeal of new releases. But they ended up with the same problem as every Hollywood studio: how can you reliably produce a constant stream of popular entertainment for a fickle audience? (Nobody knows.) Groupon posted fast growth as hundreds of thousands of local businesses tried their product. But persuading those businesses to become repeat customers was harder than they thought.

If you focus on near-term growth above all else, you miss the most important question you should be asking: will this business still be around a decade from now? Numbers alone won’t tell you the answer; instead you must think critically about the qualitative characteristics of your business.

CHARACTERISTICS OF MONOPOLY

What does a company with large cash flows far into the future look like? Every monopoly is unique, but they usually share some combination of the following characteristics: proprietary technology, network effects, economies of scale, and branding.

This isn’t a list of boxes to check as you build your business—there’s no shortcut to monopoly. However, analyzing your business according to these characteristics can help you think about how to make it durable.

- Proprietary Technology

Proprietary technology is the most substantive advantage a company can have because it makes your product difficult or impossible to replicate. Google’s search algorithms, for example, return results better than anyone else’s. Proprietary technologies for extremely short page load times and highly accurate query autocompletion add to the core search product’s robustness and defensibility. It would be very hard for anyone to do to Google what Google did to all the other search engine companies in the early 2000s.

As a good rule of thumb, proprietary technology must be at least 10 times better than its closest substitute in some important dimension to lead to a real monopolistic advantage. Anything less than an order of magnitude better will probably be perceived as a marginal improvement and will be hard to sell, especially in an already crowded market.

The clearest way to make a 10x improvement is to invent something completely new. If you build something valuable where there was nothing before, the increase in value is theoretically infinite. A drug to safely eliminate the need for sleep, or a cure for baldness, for example, would certainly support a monopoly business.

Or you can radically improve an existing solution: once you’re 10x better, you escape competition. PayPal, for instance, made buying and selling on eBay at least 10 times better. Instead of mailing a check that would take 7 to 10 days to arrive, PayPal let buyers pay as soon as an auction ended. Sellers received their proceeds right away, and unlike with a check, they knew the funds were good.

Amazon made its first 10x improvement in a particularly visible way: they offered at least 10 times as many books as any other bookstore. When it launched in 1995, Amazon could claim to be “Earth’s largest bookstore” because, unlike a retail bookstore that might stock 100,000 books, Amazon didn’t need to physically store any inventory—it simply requested the title from its supplier whenever a customer made an order. This quantum improvement was so effective that a very unhappy Barnes & Noble filed a lawsuit three days before Amazon’s IPO, claiming that Amazon was unfairly calling itself a “bookstore” when really it was a “book broker.” You can also make a 10x improvement through superior integrated design. Before 2010, tablet computing was so poor that for all practical purposes the market didn’t even exist. “Microsoft Windows XP Tablet PC Edition” products first shipped in 2002, and Nokia released its own “Internet Tablet” in 2005, but they were a pain to use. Then Apple released the iPad. Design improvements are hard to measure, but it seems clear that Apple improved on anything that had come before by at least an order of magnitude: tablets went from unusable to useful.

- Network Effects

Network effects make a product more useful as more people use it. For example, if all your friends are on Facebook, it makes sense for you to join Facebook, too. Unilaterally choosing a different social network would only make you an eccentric.

Network effects can be powerful, but you’ll never reap them unless your product is valuable to its very first users when the network is necessarily small. For example, in 1960 a quixotic company called Xanadu set out to build a two-way communication network between all computers—a sort of early, synchronous version of the World Wide Web. After more than three decades of futile effort, Xanadu folded just as the web was becoming commonplace. Their technology probably would have worked at scale, but it could have worked only at scale: it required every computer to join the network at the same time, and that was never going to happen.

Paradoxically, then, network effects businesses must start with especially small markets. Facebook started with just Harvard students—Mark Zuckerberg’s first product was designed to get all his classmates signed up, not to attract all people of Earth. This is why successful network businesses rarely get started by MBA types: the initial markets are so small that they often don’t even appear to be business opportunities at all.

- Economies of Scale

A monopoly business gets stronger as it gets bigger: the fixed costs of creating a product (engineering, management, office space) can be spread out over ever greater quantities of sales. Software startups can enjoy especially dramatic economies of scale because the marginal cost of producing another copy of the product is close to zero.

Many businesses gain only limited advantages as they grow to large scale. Service businesses especially are difficult to make monopolies. If you own a yoga studio, for example, you’ll only be able to serve a certain number of customers. You can hire more instructors and expand to more locations, but your margins will remain fairly low and you’ll never reach a point where a core group of talented people can provide something of value to millions of separate clients, as software engineers are able to do.

A good startup should have the potential for great scale built into its first design. Twitter already has more than 250 million users today. It doesn’t need to add too many customized features in order to acquire more, and there’s no inherent reason why it should ever stop growing.

- Branding

A company has a monopoly on its own brand by definition, so creating a strong brand is a powerful way to claim a monopoly. Today’s strongest tech brand is Apple: the attractive looks and carefully chosen materials of products like the iPhone and MacBook, the Apple Stores’ sleek minimalist design and close control over the consumer experience, the omnipresent advertising campaigns, the price positioning as a maker of premium goods, and the lingering nimbus of Steve Jobs’s personal charisma all contribute to a perception that Apple offers products so good as to constitute a category of their own.

Many have tried to learn from Apple’s success: paid advertising, branded stores, luxurious materials, playful keynote speeches, high prices, and even minimalist design are all susceptible to imitation. But these techniques for polishing the surface don’t work without a strong underlying substance. Apple has a complex suite of proprietary technologies, both in hardware (like superior touchscreen materials) and software (like touchscreen interfaces purpose-designed for specific materials). It manufactures products at a scale large enough to dominate pricing for the materials it buys. And it enjoys strong network effects from its content ecosystem: thousands of developers write software for Apple devices because that’s where hundreds of millions of users are, and those users stay on the platform because it’s where the apps are. These other monopolistic advantages are less obvious than Apple’s sparkling brand, but they are the fundamentals that let the branding effectively reinforce Apple’s monopoly.

Beginning with brand rather than substance is dangerous. Ever since Marissa Mayer became CEO of Yahoo! in mid-2012, she has worked to revive the once-popular internet giant by making it cool again. In a single tweet, Yahoo! summarized Mayer’s plan as a chain reaction of “people then products then traffic then revenue.” The people are supposed to come for the coolness: Yahoo! demonstrated design awareness by overhauling its logo, it asserted youthful relevance by acquiring hot startups like Tumblr, and it has gained media attention for Mayer’s own star power. But the big question is what products Yahoo! will actually create. When Steve Jobs returned to Apple, he didn’t just make Apple a cool place to work; he slashed product lines to focus on the handful of opportunities for 10x improvements. No technology company can be built on branding alone.

BUILDING A MONOPOLY

Brand, scale, network effects, and technology in some combination define a monopoly; but to get them to work, you need to choose your market carefully and expand deliberately.

Start Small and Monopolize

Every startup is small at the start. Every monopoly dominates a large share of its market. Therefore, every startup should start with a very small market. Always err on the side of starting too small. The reason is simple: it’s easier to dominate a small market than a large one. If you think your initial market might be too big, it almost certainly is.

Small doesn’t mean nonexistent. We made this mistake early on at PayPal. Our first product let people beam money to each other via PalmPilots. It was interesting technology and no one else was doing it. However, the world’s millions of PalmPilot users weren’t concentrated in a particular place, they had little in common, and they used their devices only episodically. Nobody needed our product, so we had no customers.

With that lesson learned, we set our sights on eBay auctions, where we found our first success. In late 1999, eBay had a few thousand high-volume “PowerSellers,” and after only three months of dedicated effort, we were serving 25% of them. It was much easier to reach a few thousand people who really needed our product than to try to compete for the attention of millions of scattered individuals.

The perfect target market for a startup is a small group of particular people concentrated together and served by few or no competitors. Any big market is a bad choice, and a big market already served by competing companies is even worse. This is why it’s always a red flag when entrepreneurs talk about getting 1% of a $100 billion market. In practice, a large market will either lack a good starting point or it will be open to competition, so it’s hard to ever reach that 1%. And even if you do succeed in gaining a small foothold, you’ll have to be satisfied with keeping the lights on: cutthroat competition means your profits will be zero.

Scaling Up

Once you create and dominate a niche market, then you should gradually expand into related and slightly broader markets. Amazon shows how it can be done. Jeff Bezos’s founding vision was to dominate all of online retail, but he very deliberately started with books. There were millions of books to catalog, but they all had roughly the same shape, they were easy to ship, and some of the most rarely sold books—those least profitable for any retail store to keep in stock—also drew the most enthusiastic customers. Amazon became the dominant solution for anyone located far from a bookstore or seeking something unusual. Amazon then had two options: expand the number of people who read books, or expand to adjacent markets. They chose the latter, starting with the most similar markets: CDs, videos, and software. Amazon continued to add categories gradually until it had become the world’s general store. The name itself brilliantly encapsulated the company’s scaling strategy. The biodiversity of the Amazon rain forest reflected Amazon’s first goal of cataloging every book in the world, and now it stands for every kind of thing in the world, period.

eBay also started by dominating small niche markets. When it launched its auction marketplace in 1995, it didn’t need the whole world to adopt it at once; the product worked well for intense interest groups, like Beanie Baby obsessives. Once it monopolized the Beanie Baby trade, eBay didn’t jump straight to listing sports cars or industrial surplus: it continued to cater to small-time hobbyists until it became the most reliable marketplace for people trading online no matter what the item.

Sometimes there are hidden obstacles to scaling—a lesson that eBay has learned in recent years. Like all marketplaces, the auction marketplace lent itself to natural monopoly because buyers go where the sellers are and vice versa. But eBay found that the auction model works best for individually distinctive products like coins and stamps. It works less well for commodity products: people don’t want to bid on pencils or Kleenex, so it’s more convenient just to buy them from Amazon. eBay is still a valuable monopoly; it’s just smaller than people in 2004 expected it to be.

Sequencing markets correctly is underrated, and it takes discipline to expand gradually. The most successful companies make the core progression—to first dominate a specific niche and then scale to adjacent markets—a part of their founding narrative.

Don’t Disrupt

Silicon Valley has become obsessed with “disruption.” Originally, “disruption” was a term of art to describe how a firm can use new technology to introduce a low-end product at low prices, improve the product over time, and eventually overtake even the premium products offered by incumbent companies using older technology. This is roughly what happened when the advent of PCs disrupted the market for mainframe computers: at first PCs seemed irrelevant, then they became dominant. Today mobile devices may be doing the same thing to PCs.

However, disruption has recently transmogrified into a self-congratulatory buzzword for anything posing as trendy and new. This seemingly trivial fad matters because it distorts an entrepreneur’s self-understanding in an inherently competitive way. The concept was coined to describe threats to incumbent companies, so startups’ obsession with disruption means they see themselves through older firms’ eyes. If you think of yourself as an insurgent battling dark forces, it’s easy to become unduly fixated on the obstacles in your path. But if you truly want to make something new, the act of creation is far more important than the old industries that might not like what you create. Indeed, if your company can be summed up by its opposition to already existing firms, it can’t be completely new and it’s probably not going to become a monopoly.

Disruption also attracts attention: disruptors are people who look for trouble and find it. Disruptive kids get sent to the principal’s office. Disruptive companies often pick fights they can’t win. Think of Napster: the name itself meant trouble. What kinds of things can one “nap”? Music … Kids … and perhaps not much else. Shawn Fanning and Sean Parker, Napster’s then-teenage founders, credibly threatened to disrupt the powerful music recording industry in 1999. The next year, they made the cover of Time magazine. A year and a half after that, they ended up in bankruptcy court.

PayPal could be seen as disruptive, but we didn’t try to directly challenge any large competitor. It’s true that we took some business away from Visa when we popularized internet payments: you might use PayPal to buy something online instead of using your Visa card to buy it in a store. But since we expanded the market for payments overall, we gave Visa far more business than we took. The overall dynamic was net positive, unlike Napster’s negative-sum struggle with the U.S. recording industry. As you craft a plan to expand to adjacent markets, don’t disrupt: avoid competition as much as possible.

THE LAST WILL BE FIRST

You’ve probably heard about “first mover advantage”: if you’re the first entrant into a market, you can capture significant market share while competitors scramble to get started. But moving first is a tactic, not a goal. What really matters is generating cash flows in the future, so being the first mover doesn’t do you any good if someone else comes along and unseats you. It’s much better to be the last mover—that is, to make the last great development in a specific market and enjoy years or even decades of monopoly profits. The way to do that is to dominate a small niche and scale up from there, toward your ambitious long-term vision. In this one particular at least, business is like chess. Grandmaster José Raúl Capablanca put it well: to succeed, “you must study the endgame before everything else.”

مشارکت کنندگان در این صفحه

تا کنون فردی در بازسازی این صفحه مشارکت نداشته است.

🖊 شما نیز میتوانید برای مشارکت در ترجمهی این صفحه یا اصلاح متن انگلیسی، به این لینک مراجعه بفرمایید.