سرفصل های مهم

فصل 13

توضیح مختصر

- زمان مطالعه 0 دقیقه

- سطح خیلی سخت

دانلود اپلیکیشن «زیبوک»

فایل صوتی

برای دسترسی به این محتوا بایستی اپلیکیشن زبانشناس را نصب کنید.

ترجمهی فصل

متن انگلیسی فصل

Chapter 13

SEEING GREEN

AT THE START of the 21st century, everyone agreed that the next big thing was clean technology. It had to be: in Beijing, the smog had gotten so bad that people couldn’t see from building to building—even breathing was a health risk. Bangladesh, with its arsenic-laden water wells, was suffering what the New York Times called “the biggest mass poisoning in history.” In the U.S., Hurricanes Ivan and Katrina were said to be harbingers of the coming devastation from global warming. Al Gore implored us to attack these problems “with the urgency and resolve that has previously been seen only when nations mobilized for war.” People got busy: entrepreneurs started thousands of cleantech companies, and investors poured more than $50 billion into them. So began the quest to cleanse the world.

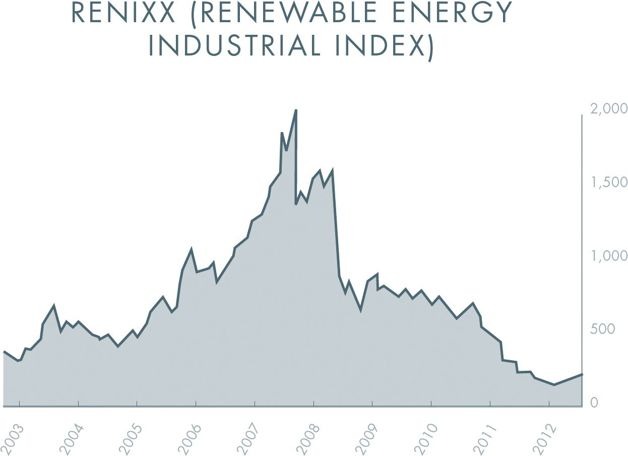

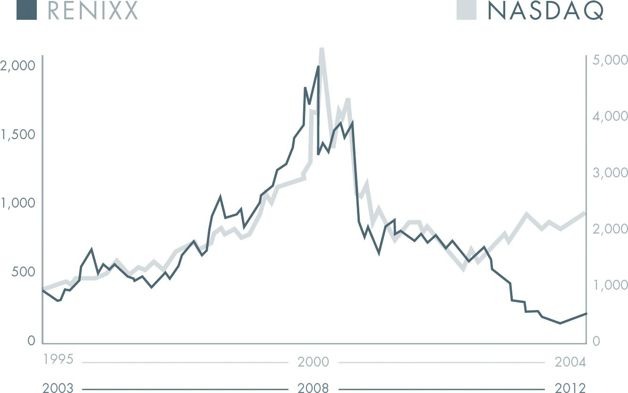

It didn’t work. Instead of a healthier planet, we got a massive cleantech bubble. Solyndra is the most famous green ghost, but most cleantech companies met similarly disastrous ends—more than 40 solar manufacturers went out of business or filed for bankruptcy in 2012 alone. The leading index of alternative energy companies shows the bubble’s dramatic deflation:

Why did cleantech fail? Conservatives think they already know the answer: as soon as green energy became a priority for the government, it was poisoned. But there really were (and there still are) good reasons for making energy a priority. And the truth about cleantech is more complex and more important than government failure. Most cleantech companies crashed because they neglected one or more of the seven questions that every business must answer: 1. The Engineering Question

Can you create breakthrough technology instead of incremental improvements?

- The Timing Question

Is now the right time to start your particular business?

- The Monopoly Question

Are you starting with a big share of a small market?

- The People Question

Do you have the right team?

- The Distribution Question

Do you have a way to not just create but deliver your product?

- The Durability Question

Will your market position be defensible 10 and 20 years into the future?

- The Secret Question

Have you identified a unique opportunity that others don’t see?

We’ve discussed these elements before. Whatever your industry, any great business plan must address every one of them. If you don’t have good answers to these questions, you’ll run into lots of “bad luck” and your business will fail. If you nail all seven, you’ll master fortune and succeed. Even getting five or six correct might work. But the striking thing about the cleantech bubble was that people were starting companies with zero good answers—and that meant hoping for a miracle.

It’s hard to know exactly why any particular cleantech company failed, since almost all of them made several serious mistakes. But since any one of those mistakes is enough to doom your company, it’s worth reviewing cleantech’s losing scorecard in more detail.

THE ENGINEERING QUESTION

A great technology company should have proprietary technology an order of magnitude better than its nearest substitute. But cleantech companies rarely produced 2x, let alone 10x, improvements. Sometimes their offerings were actually worse than the products they sought to replace. Solyndra developed novel, cylindrical solar cells, but to a first approximation, cylindrical cells are only 1/π as efficient as flat ones—they simply don’t receive as much direct sunlight. The company tried to correct for this deficiency by using mirrors to reflect more sunlight to hit the bottoms of the panels, but it’s hard to recover from a radically inferior starting point.

Companies must strive for 10x better because merely incremental improvements often end up meaning no improvement at all for the end user. Suppose you develop a new wind turbine that’s 20% more efficient than any existing technology—when you test it in the laboratory. That sounds good at first, but the lab result won’t begin to compensate for the expenses and risks faced by any new product in the real world. And even if your system really is 20% better on net for the customer who buys it, people are so used to exaggerated claims that you’ll be met with skepticism when you try to sell it. Only when your product is 10x better can you offer the customer transparent superiority.

THE TIMING QUESTION

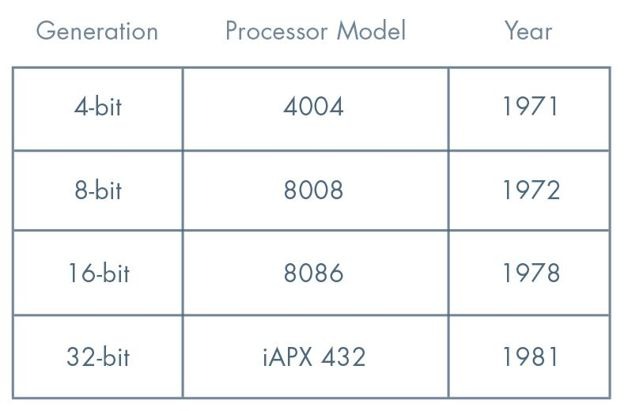

Cleantech entrepreneurs worked hard to convince themselves that their appointed hour had arrived. When he announced his new company in 2008, SpectraWatt CEO Andrew Wilson stated that “[t]he solar industry is akin to where the microprocessor industry was in the late 1970s. There is a lot to be figured out and improved.” The second part was right, but the microprocessor analogy was way off. Ever since the first microprocessor was built in 1970, computing advanced not just rapidly but exponentially. Look at Intel’s early product release history:

The first silicon solar cell, by contrast, was created by Bell Labs in 1954—more than a half century before Wilson’s press release. Photovoltaic efficiency improved in the intervening decades, but slowly and linearly: Bell’s first solar cell had about 6% efficiency; neither today’s crystalline silicon cells nor modern thin-film cells have exceeded 25% efficiency in the field. There were few engineering developments in the mid-2000s to suggest impending liftoff. Entering a slow-moving market can be a good strategy, but only if you have a definite and realistic plan to take it over. The failed cleantech companies had none.

THE MONOPOLY QUESTION

In 2006, billionaire technology investor John Doerr announced that “green is the new red, white and blue.” He could have stopped at “red.” As Doerr himself said, “Internet-sized markets are in the billions of dollars; the energy markets are in the trillions.” What he didn’t say is that huge, trillion-dollar markets mean ruthless, bloody competition. Others echoed Doerr over and over: in the 2000s, I listened to dozens of cleantech entrepreneurs begin fantastically rosy PowerPoint presentations with all-too-true tales of trillion-dollar markets—as if that were a good thing.

Cleantech executives emphasized the bounty of an energy market big enough for all comers, but each one typically believed that his own company had an edge. In 2006, Dave Pearce, CEO of solar manufacturer MiaSolé, admitted to a congressional panel that his company was just one of several “very strong” startups working on one particular kind of thin-film solar cell development. Minutes later, Pearce predicted that MiaSolé would become “the largest producer of thin-film solar cells in the world” within a year’s time. That didn’t happen, but it might not have helped them anyway: thin-film is just one of more than a dozen kinds of solar cells. Customers won’t care about any particular technology unless it solves a particular problem in a superior way. And if you can’t monopolize a unique solution for a small market, you’ll be stuck with vicious competition. That’s what happened to MiaSolé, which was acquired in 2013 for hundreds of millions of dollars less than its investors had put into the company.

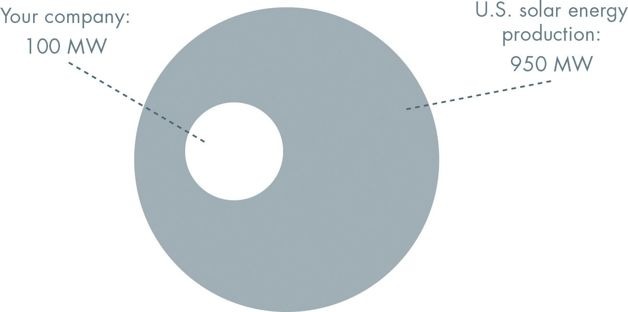

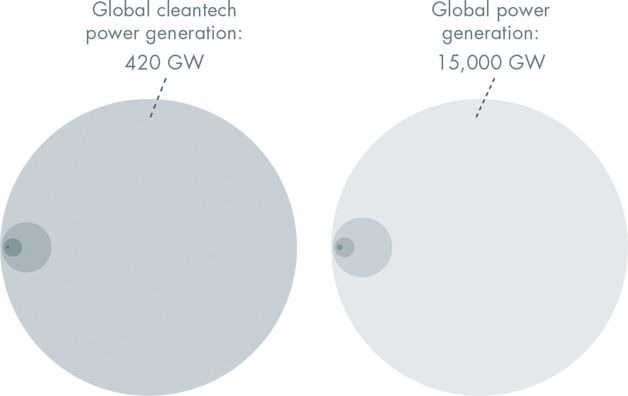

Exaggerating your own uniqueness is an easy way to botch the monopoly question. Suppose you’re running a solar company that’s successfully installed hundreds of solar panel systems with a combined power generation capacity of 100 megawatts. Since total U.S. solar energy production capacity is 950 megawatts, you own 10.53% of the market. Congratulations, you tell yourself: you’re a player.

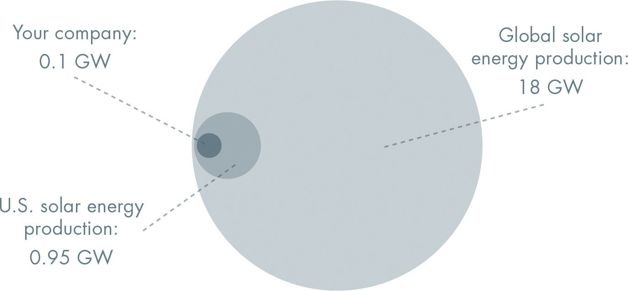

But what if the U.S. solar energy market isn’t the relevant market? What if the relevant market is the global solar market, with a production capacity of 18 gigawatts? Your 100 megawatts now makes you a very small fish indeed: suddenly you own less than 1% of the market.

And what if the appropriate measure isn’t global solar, but rather renewable energy in general? Annual production capacity from renewables is 420 gigawatts globally; you just shrank to 0.02% of the market. And compared to the total global power generation capacity of 15,000 gigawatts, your 100 megawatts is just a drop in the ocean.

Cleantech entrepreneurs’ thinking about markets was hopelessly confused. They would rhetorically shrink their market in order to seem differentiated, only to turn around and ask to be valued based on huge, supposedly lucrative markets. But you can’t dominate a submarket if it’s fictional, and huge markets are highly competitive, not highly attainable. Most cleantech founders would have been better off opening a new British restaurant in downtown Palo Alto.

THE PEOPLE QUESTION

Energy problems are engineering problems, so you would expect to find nerds running cleantech companies. You’d be wrong: the ones that failed were run by shockingly nontechnical teams. These salesman-executives were good at raising capital and securing government subsidies, but they were less good at building products that customers wanted to buy.

At Founders Fund, we saw this coming. The most obvious clue was sartorial: cleantech executives were running around wearing suits and ties. This was a huge red flag, because real technologists wear T-shirts and jeans. So we instituted a blanket rule: pass on any company whose founders dressed up for pitch meetings. Maybe we still would have avoided these bad investments if we had taken the time to evaluate each company’s technology in detail. But the team insight—never invest in a tech CEO that wears a suit—got us to the truth a lot faster. The best sales is hidden. There’s nothing wrong with a CEO who can sell, but if he actually looks like a salesman, he’s probably bad at sales and worse at tech.

Solyndra CEO Brian Harrison; Tesla Motors CEO Elon Musk

THE DISTRIBUTION QUESTION

Cleantech companies effectively courted government and investors, but they often forgot about customers. They learned the hard way that the world is not a laboratory: selling and delivering a product is at least as important as the product itself.

Just ask Israeli electric vehicle startup Better Place, which from 2007 to 2012 raised and spent more than $800 million to build swappable battery packs and charging stations for electric cars. The company sought to “create a green alternative that would lessen our dependence on highly polluting transportation technologies.” And it did just that—at least by 1,000 cars, the number it sold before filing for bankruptcy. Even selling that many was an achievement, because each of those cars was very hard for customers to buy.

For starters, it was never clear what you were actually buying. Better Place bought sedans from Renault and refitted them with electric batteries and electric motors. So, were you buying an electric Renault, or were you buying a Better Place? In any case, if you decided to buy one, you had to jump through a series of hoops. First, you needed to seek approval from Better Place. To get that, you had to prove that you lived close enough to a Better Place battery swapping station and promise to follow predictable routes. If you passed that test, you had to sign up for a fueling subscription in order to recharge your car. Only then could you get started learning the new behavior of stopping to swap out battery packs on the road.

Better Place thought its technology spoke for itself, so they didn’t bother to market it clearly. Reflecting on the company’s failure, one frustrated customer asked, “Why wasn’t there a billboard in Tel Aviv showing a picture of a Toyota Prius for 160,000 shekels and a picture of this car, for 160,000 plus fuel for four years?” He still bought one of the cars, but unlike most people, he was a hobbyist who “would do anything to keep driving it.” Unfortunately, he can’t: as the Better Place board of directors stated upon selling the company’s assets for a meager $12 million in 2013, “The technical challenges we overcame successfully, but the other obstacles we were not able to overcome.” THE DURABILITY QUESTION

Every entrepreneur should plan to be the last mover in her particular market. That starts with asking yourself: what will the world look like 10 and 20 years from now, and how will my business fit in?

Few cleantech companies had a good answer. As a result, all their obituaries resemble each other. A few months before it filed for bankruptcy in 2011, Evergreen Solar explained its decision to close one of its U.S. factories: Solar manufacturers in China have received considerable government and financial support.… Although [our] production costs … are now below originally planned levels and lower than most western manufacturers, they are still much higher than those of our low cost competitors in China.

But it wasn’t until 2012 that the “blame China” chorus really exploded. Discussing its bankruptcy filing, U.S. Department of Energy–backed Abound Solar blamed “aggressive pricing actions from Chinese solar panel companies” that “made it very difficult for an early stage startup company … to scale in current market conditions.” When solar panel maker Energy Conversion Devices failed in February 2012, it went beyond blaming China in a press release and filed a $950 million lawsuit against three prominent Chinese solar manufacturers—the same companies that Solyndra’s trustees in bankruptcy sued later that year on the grounds of attempted monopolization, conspiracy, and predatory pricing. But was competition from Chinese manufacturers really impossible to predict? Cleantech entrepreneurs would have done well to rephrase the durability question and ask: what will stop China from wiping out my business? Without an answer, the result shouldn’t have come as a surprise.

Beyond the failure to anticipate competition in manufacturing the same green products, cleantech embraced misguided assumptions about the energy market as a whole. An industry premised on the supposed twilight of fossil fuels was blindsided by the rise of fracking. In 2000, just 1.7% of America’s natural gas came from fracked shale. Five years later, that figure had climbed to 4.1%. Nevertheless, nobody in cleantech took this trend seriously: renewables were the only way forward; fossil fuels couldn’t possibly get cheaper or cleaner in the future. But they did. By 2013, shale gas accounted for 34% of America’s natural gas, and gas prices had fallen more than 70% since 2008, devastating most renewable energy business models. Fracking may not be a durable energy solution, either, but it was enough to doom cleantech companies that didn’t see it coming.

THE SECRET QUESTION

Every cleantech company justified itself with conventional truths about the need for a cleaner world. They deluded themselves into believing that an overwhelming social need for alternative energy solutions implied an overwhelming business opportunity for cleantech companies of all kinds. Consider how conventional it had become by 2006 to be bullish on solar. That year, President George W. Bush heralded a future of “solar roofs that will enable the American family to be able to generate their own electricity.” Investor and cleantech executive Bill Gross declared that the “potential for solar is enormous.” Suvi Sharma, then-CEO of solar manufacturer Solaria, admitted that while “there is a gold rush feeling” to solar, “there’s also real gold here—or, in our case, sunshine.” But rushing to embrace the convention sent scores of solar panel companies—Q-Cells, Evergreen Solar, SpectraWatt, and even Gross’s own Energy Innovations, to name just a few—from promising beginnings to bankruptcy court very quickly. Each of the casualties had described their bright futures using broad conventions on which everybody agreed. Great companies have secrets: specific reasons for success that other people don’t see.

THE MYTH OF SOCIAL ENTREPRENEURSHIP

Cleantech entrepreneurs aimed for more than just success as most businesses define it. The cleantech bubble was the biggest phenomenon—and the biggest flop—in the history of “social entrepreneurship.” This philanthropic approach to business starts with the idea that corporations and nonprofits have until now been polar opposites: corporations have great power, but they’re shackled to the profit motive; nonprofits pursue the public interest, but they’re weak players in the wider economy. Social entrepreneurs aim to combine the best of both worlds and “do well by doing good.” Usually they end up doing neither.

The ambiguity between social and financial goals doesn’t help. But the ambiguity in the word “social” is even more of a problem: if something is “socially good,” is it good for society, or merely seen as good by society? Whatever is good enough to receive applause from all audiences can only be conventional, like the general idea of green energy.

Progress isn’t held back by some difference between corporate greed and nonprofit goodness; instead, we’re held back by the sameness of both. Just as corporations tend to copy each other, nonprofits all tend to push the same priorities. Cleantech shows the result: hundreds of undifferentiated products all in the name of one overbroad goal.

Doing something different is what’s truly good for society—and it’s also what allows a business to profit by monopolizing a new market. The best projects are likely to be overlooked, not trumpeted by a crowd; the best problems to work on are often the ones nobody else even tries to solve.

TESLA: 7 FOR 7

Tesla is one of the few cleantech companies started last decade to be thriving today. They rode the social buzz of cleantech better than anyone, but they got the seven questions right, so their success is instructive: TECHNOLOGY. Tesla’s technology is so good that other car companies rely on it: Daimler uses Tesla’s battery packs; Mercedes-Benz uses a Tesla powertrain; Toyota uses a Tesla motor. General Motors has even created a task force to track Tesla’s next moves. But Tesla’s greatest technological achievement isn’t any single part or component, but rather its ability to integrate many components into one superior product. The Tesla Model S sedan, elegantly designed from end to end, is more than the sum of its parts: Consumer Reports rated it higher than any other car ever reviewed, and both Motor Trend and Automobile magazines named it their 2013 Car of the Year.

TIMING. In 2009, it was easy to think that the government would continue to support cleantech: “green jobs” were a political priority, federal funds were already earmarked, and Congress even seemed likely to pass cap-and-trade legislation. But where others saw generous subsidies that could flow indefinitely, Tesla CEO Elon Musk rightly saw a one-time-only opportunity. In January 2010—about a year and a half before Solyndra imploded under the Obama administration and politicized the subsidy question—Tesla secured a $465 million loan from the U.S. Department of Energy. A half-billion-dollar subsidy was unthinkable in the mid-2000s. It’s unthinkable today. There was only one moment where that was possible, and Tesla played it perfectly.

MONOPOLY. Tesla started with a tiny submarket that it could dominate: the market for high-end electric sports cars. Since the first Roadster rolled off the production line in 2008, Tesla’s sold only about 3,000 of them, but at $109,000 apiece that’s not trivial. Starting small allowed Tesla to undertake the necessary R&D to build the slightly less expensive Model S, and now Tesla owns the luxury electric sedan market, too. They sold more than 20,000 sedans in 2013 and now Tesla is in prime position to expand to broader markets in the future.

TEAM. Tesla’s CEO is the consummate engineer and salesman, so it’s not surprising that he’s assembled a team that’s very good at both. Elon describes his staff this way: “If you’re at Tesla, you’re choosing to be at the equivalent of Special Forces. There’s the regular army, and that’s fine, but if you are working at Tesla, you’re choosing to step up your game.” DISTRIBUTION. Most companies underestimate distribution, but Tesla took it so seriously that it decided to own the entire distribution chain. Other car companies are beholden to independent dealerships: Ford and Hyundai make cars, but they rely on other people to sell them. Tesla sells and services its vehicles in its own stores. The up-front costs of Tesla’s approach are much higher than traditional dealership distribution, but it affords control over the customer experience, strengthens Tesla’s brand, and saves the company money in the long run.

DURABILITY. Tesla has a head start and it’s moving faster than anyone else—and that combination means its lead is set to widen in the years ahead. A coveted brand is the clearest sign of Tesla’s breakthrough: a car is one of the biggest purchasing decisions that people ever make, and consumers’ trust in that category is hard to win. And unlike every other car company, at Tesla the founder is still in charge, so it’s not going to ease off anytime soon.

SECRETS. Tesla knew that fashion drove interest in cleantech. Rich people especially wanted to appear “green,” even if it meant driving a boxy Prius or clunky Honda Insight. Those cars only made drivers look cool by association with the famous eco-conscious movie stars who owned them as well. So Tesla decided to build cars that made drivers look cool, period—Leonardo DiCaprio even ditched his Prius for an expensive (and expensive-looking) Tesla Roadster. While generic cleantech companies struggled to differentiate themselves, Tesla built a unique brand around the secret that cleantech was even more of a social phenomenon than an environmental imperative.

ENERGY 2.0

Tesla’s success proves that there was nothing inherently wrong with cleantech. The biggest idea behind it is right: the world really will need new sources of energy. Energy is the master resource: it’s how we feed ourselves, build shelter, and make everything we need to live comfortably. Most of the world dreams of living as comfortably as Americans do today, and globalization will cause increasingly severe energy challenges unless we build new technology. There simply aren’t enough resources in the world to replicate old approaches or redistribute our way to prosperity.

Cleantech gave people a way to be optimistic about the future of energy. But when indefinitely optimistic investors betting on the general idea of green energy funded cleantech companies that lacked specific business plans, the result was a bubble. Plot the valuation of alternative energy firms in the 2000s alongside the NASDAQ’s rise and fall a decade before, and you see the same shape:

The 1990s had one big idea: the internet is going to be big. But too many internet companies had exactly that same idea and no others. An entrepreneur can’t benefit from macro-scale insight unless his own plans begin at the micro-scale. Cleantech companies faced the same problem: no matter how much the world needs energy, only a firm that offers a superior solution for a specific energy problem can make money. No sector will ever be so important that merely participating in it will be enough to build a great company.

The tech bubble was far bigger than cleantech and the crash even more painful. But the dream of the ’90s turned out to be right: skeptics who doubted that the internet would fundamentally change publishing or retail sales or everyday social life looked prescient in 2001, but they seem comically foolish today. Could successful energy startups be founded after the cleantech crash just as Web 2.0 startups successfully launched amid the debris of the dot-coms? The macro need for energy solutions is still real. But a valuable business must start by finding a niche and dominating a small market. Facebook started as a service for just one university campus before it spread to other schools and then the entire world. Finding small markets for energy solutions will be tricky—you could aim to replace diesel as a power source for remote islands, or maybe build modular reactors for quick deployment at military installations in hostile territories. Paradoxically, the challenge for the entrepreneurs who will create Energy 2.0 is to think small.

مشارکت کنندگان در این صفحه

تا کنون فردی در بازسازی این صفحه مشارکت نداشته است.

🖊 شما نیز میتوانید برای مشارکت در ترجمهی این صفحه یا اصلاح متن انگلیسی، به این لینک مراجعه بفرمایید.